This is not my Country

This is not my Country, and because it’s not my Country, I cannot speak on its behalf. This statement is true for me, and almost every built environment professional in Australia, so how can we work on and with the Countries that we are responsible for fundamentally modifying?

Almost every piece of literature I have read on this topic, across a broad range of professions, makes the key and crucial point that relationship building is at the centre of working with Indigenous Australians, their cultural materials and the Countries they are custodians of. The challenge of course, is that we live in a country with many histories that haven’t been told and many of the associated protocols and customs of cultures that haven’t become ingrained in our collective understanding of the places we live.

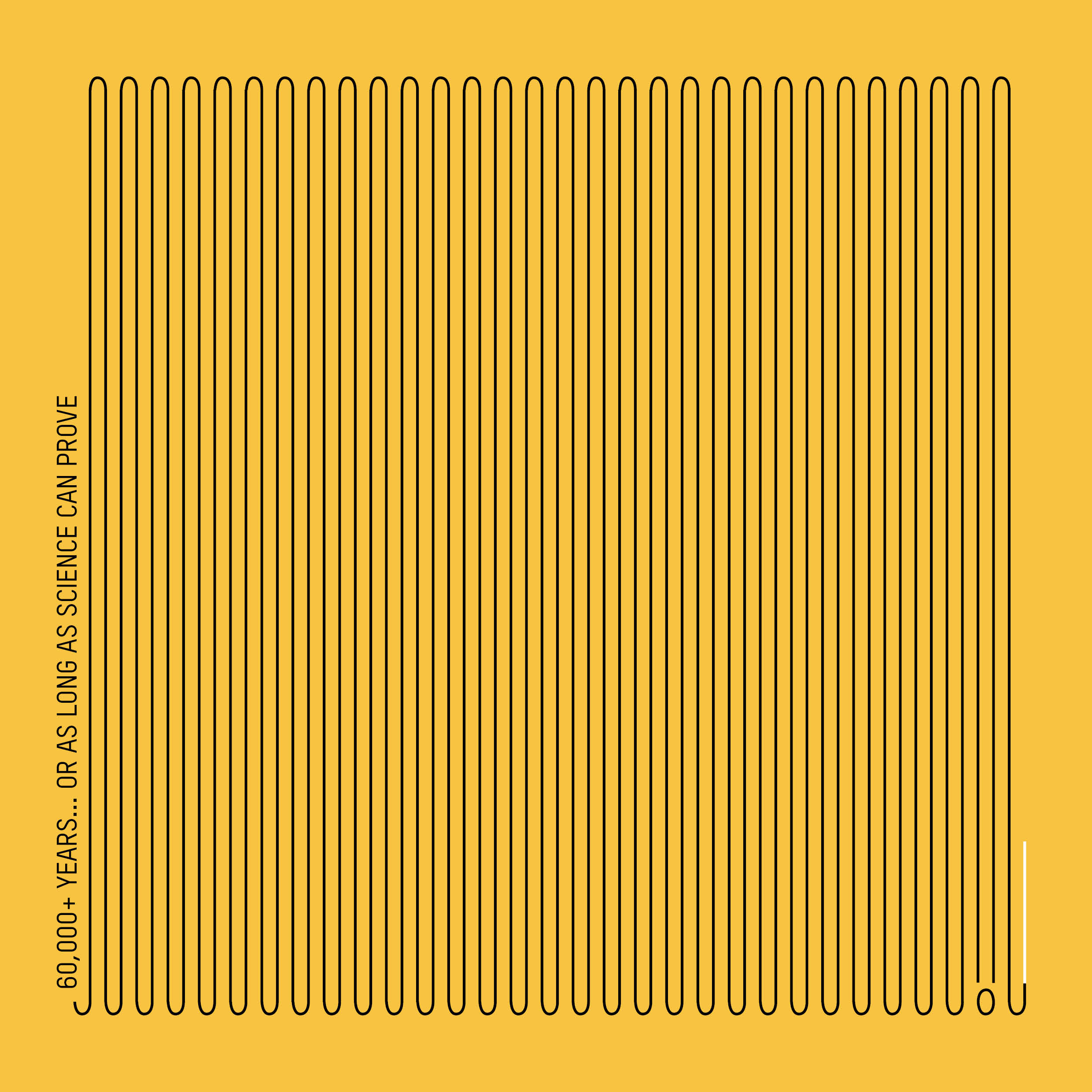

Consequentially, we don’t know what is appropriate and we don’t know our own heritage. This is slowly changing, and so too is the attitude towards how we commonly define heritage. Indigenous peoples don’t memorialise history in the same way as Western books and museums. Our histories are living, they are continuous, and they are always with us. They are kept alive by rituals, ethics and behaviours that ensure continuance and respect. I define these behaviours as protocols.

Protocols in this sense are a code of behaviour embedded with actions, ethics and nuanced socio-political understanding. The protocols of interaction with people and place vary greatly across Australia and the world; however, they are central to building relationships across cultures. They aren’t new, they are part of our heritage and they are constantly remapped and adapted in response to change. The remapping of protocols has been manifested in many papers, guidelines and policies, each of which tackle either the outcomes or processes for specific professions. So, the question becomes, how do these protocols relate to architecture and the built environment?

What are the protocols we can follow when working on someone else’s Country? I presented some of the protocols we follow at the 2019 Australian Institute of Architects National Architecture Conference in Melbourne. Some of these protocols are inherited, some are learned and some reference protocols from other professions that are relevant to our own. This isn’t a definitive list, nor is it necessarily relevant for every project or everywhere in Australia.

The intention of sharing these at the conference and again in this article is to touch on some points that may help navigate a way through built environment processes that respects and honours Indigenous Australian communities and their Countries. The following protocols are mapped to the stages of architecture. This article will draw together learnings from a selection of protocols within the internal, procurement and design stages.

Australia is a conglomerate of hundreds of different language groups, otherwise known as Countries. Traditional Owners have inherited the rights and the knowledge of their Country and therefore are the only people who hold the cultural authority to speak on its behalf. It is important to know the Country you and/or your project are on, so that you can engage with the right communities.

In Victoria, a starting point for understanding which Country you are on is the Registered Aboriginal Parties map on the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council website. This is not a complete list as many communities may be in the process of or are yet to register.

Also note that Country is not just land. In fact, it’s not just land, water and sky either; it is every element of nature including their associated and interconnected systems. This includes humans. We can’t separate ourselves from the system, we can only work with it or against it. Understanding this ethic and the systems and stories of Country is Indigenous Knowledge.

In a Western education system you have a right to knowledge. Almost everything you want to know is accessible to you. In an Indigenous context, you earn knowledge over your lifetime when you have proven you will be responsible with its legacy and INTERNAL PROTOCOLS: Know who you are and where you come from. Know whose Country you are on. Educate yourself with Indigenous perspectives. Understand the way Knowledge works. Be introspective: motivation and intent. Be fearless. Eliminate elitism, expectation and egotism. PROCUREMENT PROTOCOLS: Indigenous-led. Co-design engagement. Make it official. Facilitate empowerment. Facilitate relationships. DESIGN PROCESS PROTOCOLS: Build in a feedback loop. Listen first. Creative suggestions, ask, don’t tell. Layer cultural representation. CONSTRUCTION PROTOCOLS: Breaking ground. Bring the community with you. POST OCCUPATION PROTOCOLS: Ask for feedback and share what you’ve learned. Update your protocol list and encourage post-occupancy evaluation AWARDS AND MEDIA PROTOCOLS: Measuring good Indigenous design. Be accountable for its continuation. Or when it is deemed you need to know something.

As such, don’t expect Traditional Owners to hand over Knowledge, no matter what project you are undertaking or the status of your relationship with a Traditional Owner. At the start of any new project you will likely be greeted with skepticism, you will be tested and your motivations questioned. This is due to both the responsibility inherent in holding and transferring Knowledge, and the negative legacy of appropriation and disenfranchisement many communities have experienced (and continue to experience) for the last 200-plus years.

Before embarking on working with Traditional Owners, go through a process of self-education to supplement any teaching you may or may not have received. The limitations of our education are not our individual faults, we didn’t design the curriculums we grew up in; however, it is now your responsibility to seek out this learning.

The key to this approach is to ensure you are learning from the right people. Look for resources that have been delivered, authored, designed or co-designed with Traditional Owners of the relevant Country. Start conversations with Traditional Owners during the procurement stage so that there is time to embed the values of Country and community into your project. Understand, however, that this self-education will never make you an expert.

At university, a lecturer defined architects as master builders, taught to speak as if we are experts and explain our buildings as if there are no flaws in the process or the outcome – to give the illusion we know everything so that clients have confidence in our ability to tackle a variety of constraints and aspirations. Approaching working with Traditional Owners with the elitism, expectation and egotism anticipated by my university lecturer is not going to get you very far. It’s difficult to feel respected if you get the sense you are being considered lesser, your knowledge isn’t valued or its understanding is being limited, simplified or romanticised, or you are being talked over or not listened to.

As an industry, we need to value Indigenous Knowledge, because it can only improve what we create through design, sustainability, caring for Country and for humanity.

A number of tools exist to facilitate respect for Traditional Owners and Knowledge of Country. One of these is the International Indigenous Design Charter. A term popularised by the charter and now used quite frequently is the term ‘Indigenous led’.

Professor Brian Martin, a co-author of the charter recently described Indigenous-led as leading with Indigenous voices, which means when the project is being dreamed up or a brief is being developed, Traditional Owner voices are embedded from the start. The charter is freely available online and includes a series of ten protocols.

Ultimately, the best way to find out what works best for a community is to ask the community. In my experience for example, some Traditional Owners will want a senior elder to represent them, some will want a cross-section of the community to be present, some have multiple family or clan groups within a single language group and for the process to be robust and meaningful there needs to be representatives from each group.

As mentioned earlier, the relationship between designer and Traditional Owner is important, especially as we are being entrusted to translate knowledge, cultural representation, social dynamic or politic that has been shared with us into a built environment. However, if the Traditional Owner is not the client then the most important relationship that needs to develop over the course of the project is that of the end user and Traditional Owner. Once we put down our pens (or mouse), and the builders down tools, we are no longer an everyday part of the project. Therefore, the site-based ongoing relationship is between the end user and the Traditional Owners. For that to be meaningful, where possible start in procurement and continue throughout the entire project in perpetuity regardless of the project type.

Projects exist on a spectrum or matrix: at one end being Traditional Owner client, Traditional Owner stakeholders and Traditional Owner end users. At the other end, non-Indigenous client, non-Indigenous stakeholders and non-Indigenous end users. Each possible combination possesses a unique capacity to engage and facilitate community empowerment.

Nightingale’s incorporation of the Pay the Rent scheme is one example of a project where there is no guarantee that the clients, stakeholders or end users will be Indigenous; however, reciprocity in the form of financial empowerment for Traditional Owners are embedded into the multi-residential housing model in an ongoing capacity, regardless of its makeup.

It is important to clarify that the kind of empowerment and engagement we are talking about here is not cultural heritage management plans, triggered by development overlays and subsequent archaeological processes.

These processes are incredibly important, but every kind of project has the potential to engage at a level that is not just looking backwards but also looking forwards, or rather, closes the loop. This could mean developing a memorandum or statement of understanding that articulates your reciprocal responsibilities and the process for engagement with a particular language group.

Governments, developers and peak industry bodies could undertake this in an open and ongoing capacity with inbuilt mechanisms to review on a regular basis. The example of a benefit with this approach is that expectations can be worked out with communities from the beginning and appropriate time can be built into the process for internal community review and approval processes.

A great reference for legal frameworks and approaches is the work of Terri Janke, an Indigenous solicitor, specialising in Indigenous cultural and intellectual property.

Whether or not you have a formal engagement plan, build in a feedback loop. This process at a minimum involves multiple face-to-face engagements. It is integral that where Knowledge has been shared and translated into design there is an ongoing engagement to ensure what the designer has heard, and subsequently translated into the design, is appropriate to its cultural and geographic context. Cultural representation in design needs to be layered and operating on many levels.

The common narrative is that we’ve moved on from no representation to sticking a dot painting on the wall, to embedding a motif into a textile or surface and now perhaps, working towards a spatial response to protocols. What we need is greater understanding of the potential Indigenous Knowledge and cultural practice can bring to design.

If we presume it can only be a painting or a textile pattern response, for example, then we are automatically limiting what we could achieve together. Sometimes, however, that could be the best response. There are so many ways we could shift how we think about design to open up new opportunities.

For example, what if landscape designs were undertaken from the lens of habitat rather than ornament? What if we could facilitate cultural practices such as weaving by ensuring the correct plant species are incorporated into the design and rights to their cultivation agreed with Traditional Owners? What if we designed for other than human? What if we recognise the significance of a moiety or totem of a local area by designing a built environment that encourages their return to that environment, rather than an abstract interpretation of said moiety or totem, or perhaps both?

What if we used materials that are contextual to Country, for example bluestone is prevalent in western Victoria but what would an appropriate material response be for the CBD? What if we could tell the history of a place without plaques or western memorials? How can the design and construction of built environments encourage young Indigenous people into design?

What if we employed a hierarchy of local, regional, national, international, into our material and supply decision making? What if we considered Indigenous cultural representation as an opportunity for joy and celebration?

What if the built environment we create is a place where Elders can bring their young people to learn about Country within the city? The list of opportunities is endless. The point being, there is a place for all forms of cultural representation in design.

Different people from community will see themselves reflected in different aspects of the design. Overwhelmingly, at the moment we are progressively designing cities and buildings that look like they could be anywhere.

Indigenous Knowledge in design is an opportunity to create environments that couldn’t be from anywhere else because they embrace and celebrate the unique identity that exists in every Country across Australia. These identities of place hold the shared cultures and protocols of both our heritage and our future. Our responsibility is to act in alignment with these protocols to ensure our heritage continues living throughout the environment we shape.

Sarah Lynn Rees is a Palawa woman descending from the Plangermaireener and Trawlwoolway people of north-east Tasmania. Associate and Indigenous advisory lead at Jackson Clements Burrows, Sarah also manages the MPavilion Blakitecture series. She holds an MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design from the University of Cambridge and is co-chair of the Australian Institute of Architects First Nations Advisory Working Group and Cultural Reference Panel.

Published online:

16 Sep 2021

Source:

Architect Victoria

Re-valuing Heritage

Summer 2020