Matsuyama + architect Hiroshi Sambuichi

Although born and raised in Japan, being a zainichi Korean Japanese with a Korean surname has always made me question the relationship between my racial identity, nationality and cultural heritage. In a country where anyone with a non-Japanese name is assumed to be a foreigner, I have embraced Japanese culture and philosophy and feel Japanese, regardless of people’s perceptions. In Australia, where everyone has a unique background, I feel accepted as a person with Japanese heritage. Furthermore, deep connections with Australian architects with Japanese philosophy at their heart has made me better appreciate my cultural heritage.

Introducing my Matsuyama

I arrived in Australia with one suitcase in 2011, straight after finishing primary school in rural Japan. My Japanese language within the English-only environment was helped by haiku poetry. My hometown, Matsuyama, on Shikoku Island, is known as the City of Haiku, with heritage architecture associated with notable haiku poets. Since I was ten years old, haiku became a way of seeing the world – infusing my own sensory experience into the observation of everyday life in 17 syllables. The practice of weaving seasonal words into haiku – learning myriads of names for rain, clouds, air and light – led me to be mindful of changes in the landscape, ultimately informing how I approach architecture.

Whenever I return home to Matsuyama, I visit Dogo, an old part of the city, known for one of Japan’s three oldest hot springs, Dogo Onsen. The district encompasses Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, several bathhouses, a castle ruin and rampart gardens, as well as the Shiki Museum, where haiku poets gather together on special occasions. It is not necessarily the individual buildings, but sensory memories of historical architecture – the smoothness of timber grains, the softness of bath water and the resonance of stone steps – that engender a continuum of time of Dogo within me. Praying at Isaniwa Shrine in the New Year, appreciating cherry blossom season in Dogo Park (Yuzuki Castle ruin), and cleaning my family gravestones at Hogonji Temple deepened my relationship with the district over time, even since moving to Australia.

Introducing architect Hiroshi Sambuichi

Across the Seto Inland Sea from my hometown on Shikoku Island is the mainland city of Hiroshima, where Hiroshi Sambuichi practices. His projects focus on inviting people to understand the forces of nature. Architecture of the Inland Sea is his exhibition catalogue, a reflection of his deep understanding of the Seto Inland Sea, the landscape that, although close to my hometown, I knew only on a superficial level. The book has become a portal into rediscovering the landscape in place of visiting in person.

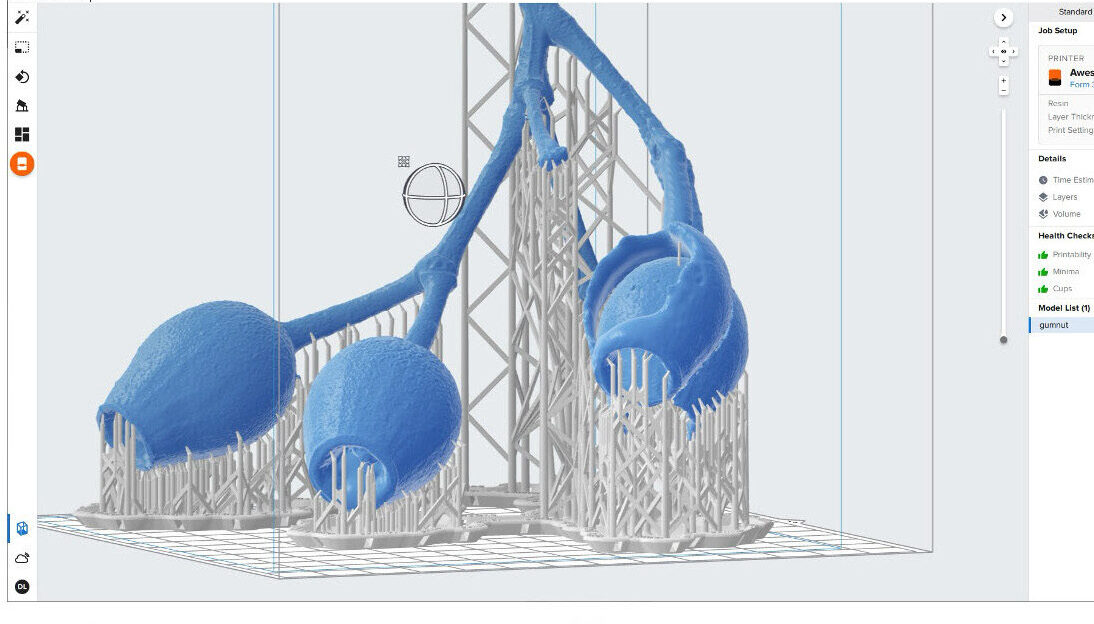

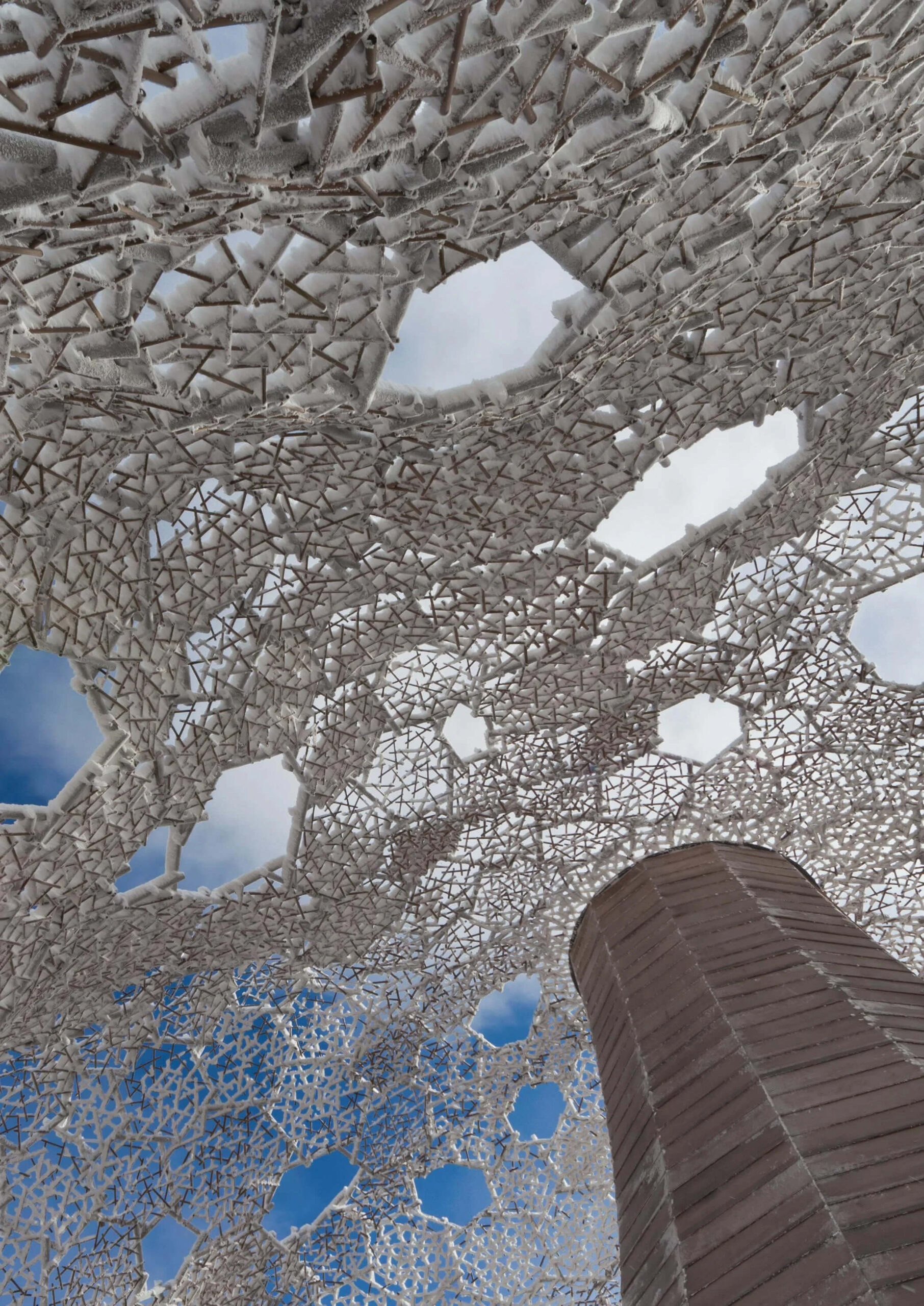

The catalogue introduces the Rokko Shidare Observatory (Kobe, Hyogo, 2010) – two hand-sketched sections (summer and winter) showing Mt Rokko, Kobe, the Seto Inland Sea and Shikoku Island illustrate the movement of water to Mt Rokko is enabled by the sun and winds. Focusing on the unique appearance of frost (soft rime) in winter, the catalogue investigates the condition for the ice to grow – when the air with almost 100% humidity, at below five-degrees temperature, collides with an object at approximately five metres per second. A veil of short wooden sticks are effective in retaining moisture for frost to grow on the observatory while letting air through.

The catalogue portrays Sambuichi’s architecture as a series of gentle gestures taking care of place and its microclimate referring to how the Seto Inland Sea and surrounding landscape, including winds, water and the sun, have always been moving and continue to move. His architecture is rational yet poetic, contemporary yet deeply rooted in the memories of the landscape. Sambuichi’s observation of landscape resonates with haiku – situating human experience in nature and admiring a moment in time, and helps me better read, understand and appreciate the sea that is so close to my home.

Saran Kim RAIA Grad. is a graduate of architecture at Architectus and a research assistant at the University of Melbourne.