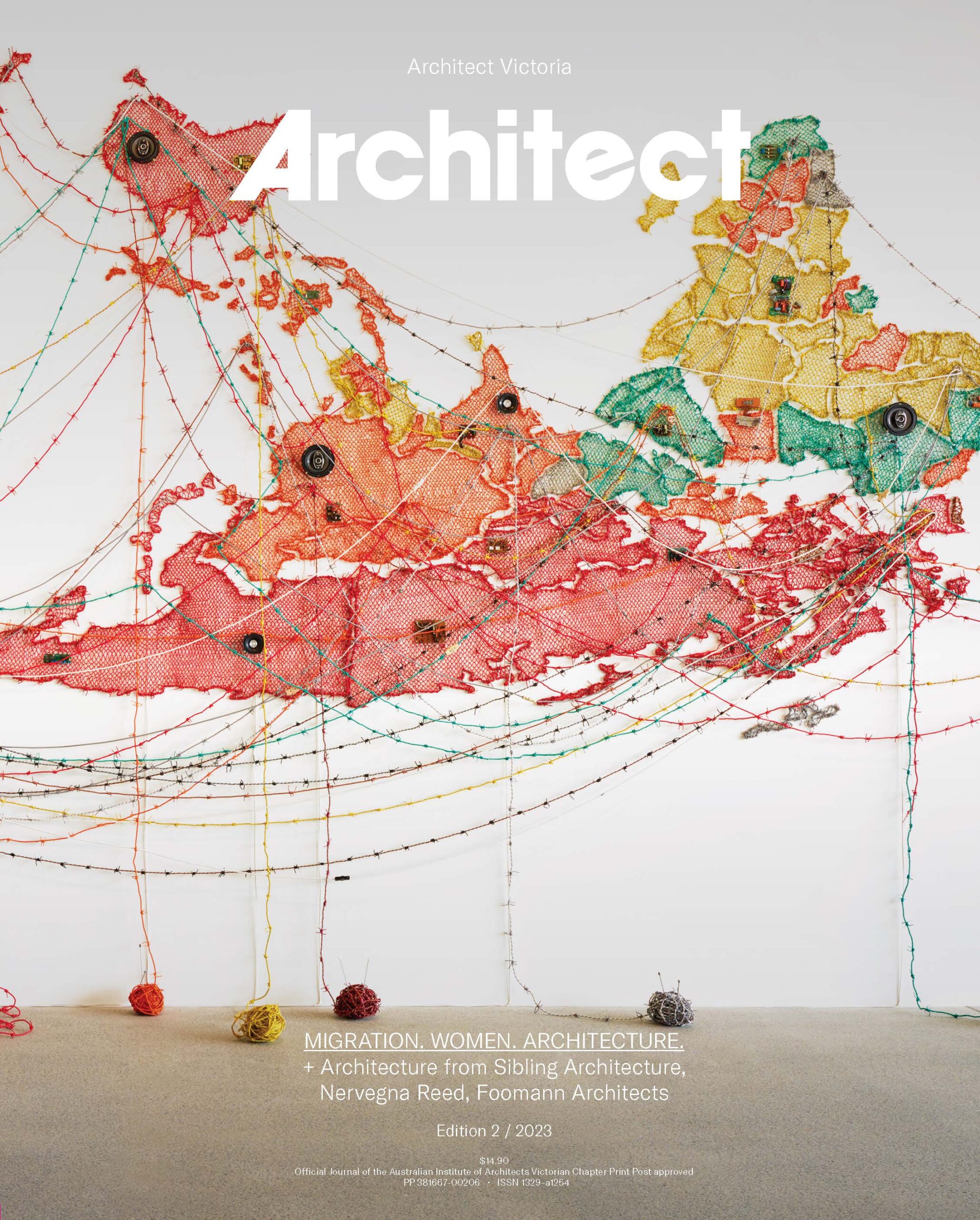

Tehran + architect Kamran Diba

My sister Sepideh was born independent and a free spirit. She left Iran for tertiary education, first to Malaysia and then to Australia. After a month, at the age of 18, I followed in her footsteps. I had been fascinated by the world of colour and form. I remained curious about how such universal elements can help us relate and connect, so for my university pathway, I chose architecture.

Introducing my Tehran

I am from the city of Tehran, Iran. Tehran is a busy metropolis with densely packed housing and small galleries, parks, cafes and restaurants in the pockets of every main street. A stroll around Tajrish or Valiasr neighbourhood, and you might come across a cafe run by a few philosophy students, filled with books you have yet to hear of, piled on top of each other from floor to ceiling. You might start a passionate discussion in the adjacent gallery and walk out as friends with a stranger.

Among these urban pockets, a series of green urban parks are important places of public life; this is where locals escape the pollution and smog, have picnics and meander. Sometimes there is music, people play the guitar within the foliage, and others gather and sing along.

I have fond memories of Shafagh Park and Community Centre, located in central Tehran, Yousefabad Neighbourhood. I remember attending art classes followed by running around the green pathways. Designed by Kamran Diba, a seminal late modernist based in Tehran, this magical project integrates existing historic buildings with planned park environments. Here densely planted landscape, urban networks, plaza and community facilities coalesce.

Introducing architect Kamran Diba

Trained at Howard University, Washington, DC, including studies in sociology, Kamran Diba returned to Iran with the ambition to put local culture and people at the centre of his projects. While Shafagh Park was among Diba’s significant early works, his design of Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA, 1977), presents an important example of late modernism in Iran. For me, another memorable place of childhood outings. Located next to Laleh Park, the project is among the best-known cultural projects realised during the final years of the Pahlavi regime. Sponsored by Farah Pahlavi, Queen of Iran from 1959-1979, it attests to her patronage of art and culture as the necessary pillars of modernisation. In her view, TMoCA was to place Iran and Iranian contemporary art on par with Western counterparts. To achieve this, she commissioned Diba, also her cousin, who shared her belief in the capacity of architecture to create an elevated environment for social and cultural engagement. Their collaboration was backed by unprecedented investment in architecture and art acquisitions.

I first visited TMoCA when I was six years old, accompanied by my family. It was a crisp autumn day in November, and the museum was an oasis of tranquillity within the urban bustle. At the entryway hordes of art students with creative colourful clothes, sat on the ground sketching. I vividly recall the Matter and Mind (Oil Pool) by the Japanese artist Noriyuki Haraguchi dramatically displayed in the museum’s atrium. The pool differed from the blue, happy pools I knew; it was black, reflective, and tense – provocative! In this palace dedicated to culture, I recall feeling the transformative power of art, inviting you to see the world afresh. Looking back at the work through an architectural lens I see vernacular references. The traditional architecture of Iranian desert towns, with playful and undulating volumetric roofscapes, below ground section that provides protection from the heat and open courtyards that both separate and connect various exhibition spaces. Filtered light animates this interior, and golden reflections bounce off the copper-clad spiral walls to guide visitors along.

Golbarg Shokrpur is a project manager at SEMZ property advisory and project management.