Lisbon is a living museum – a city that reveals a rich tapestry of historical and political aspirations through its architecture. Layers of time coexist in the stratum of the city, shaping its character and identity. Today we were guided by a local Portuguese architect Rodrigo Lima to visit about 20 buildings. From the ancient to the modern, it was fascinating to experience an urban setting that carries a deeper sense of place and time. Instead of describing every building, here are a few reflections:

- What collective memories do we want to cherish in the fabric of our cities?

The São Jorge Castle Archaeological Centre by Carrilho da Graça Arquitectos invites visitors to experience ruins unearthed during carpark excavations for the castle. This project was phenomenal. Stabilised by Corten sheets, the site reveals structures from the Iron Age, allowing visitors to contemplate the diverse occupation of this site over thousands of years. White, thick floating walls seem to hover over the perimeter of medieval remains. Original limestone and basalt foundations are complemented by honed slabs of pink stone for circulation thresholds. Citronella has been planted in the courtyards to prevent the bees from eating away at the remaining frescoes. What we keep and how we keep or frame existing materials speaks to our values.

- Architecture is long-term ephemera and, on scale, contributes to cities in flux.

The Thalia Theatre by Gonçalo Byrne and Barbas Lopes is an impressive renovation which demonstrates how architecture can exist as long-term ephemera. Yellow-tinted concrete walls, poured 15 years ago, serve to brace the original 1840s theatre structure. Walking through the sequence of spaces, there is a sense that either approach is defined by completely different characters like a two-headed Janus. At one end there is a white entrance designed by Voigt in the 1930s, lined with limestone and white interiors, inscribed with ‘Here the Deeds of Men Shall Be Punished’ in Latin over the lintel. At the other end is a contemporary glazed addition with chrome metal interiors and yellow concrete floors, built to the original building height datum where ruins could not be retained. Walking through this complex of appended spaces, the characters shifted so quickly like a Chinese face mask changing performer. The sequence of spaces is certainly theatrical and demonstrates how architecture can be reframed as long-term ephemera, a construction that changes over time.

- Let’s be more ambitious with our building life spans.

As several countries such as Finland and Denmark transition into mandating maximum carbon footprints for the construction and usage of developments, I couldn’t help but think that the 16th century Casa dos Bicos museum that was extended in the 1980s has far outlived the nominal 50-year life span of a building. Lisbon has been a powerful reminder that adaptive reuse is a powerful strategy to minimise impact and prolong the utility of materials, whilst celebrating cherished buildings.

- It’s possible for multiple architects and stylistic periods to “sing in a choir.”

Despite being shaped by various architects and periods, Lisbon maintains a cohesive character. In Helsinki, Edwina shared a memorable quote from Playa Architects, alluding to the idea that buildings can sing together more like a choir. Walking through the Alfama and Chiado neighbourhoods, I was impressed by the consistency of dwellings in their architectural language, expression and materials, despite being composited by many different architects over time.

Lisbon is one of the oldest cities in the world and demonstrates that multiple architectural styles and revised city plans (in the aftermath of natural disasters) can still resonate with one another. The result is a series of related yet distinct neighbourhood and precinct characters that contribute to an urban setting deeply rooted to its history.

- Architecture can be a testament to care, and what we care about.

The Church of Sagrado Coração de Jesus, designed by Nuno Teotonio Pereira and Nuno Portas, aimed to be an open and welcoming community space. However, its Brutalist architecture felt oppressive, contrasting with the churches we visited in Helsinki, which embraced natural light and lighter materials. Architecture can express care and reflect the values of the community it serves.

Also in today’s walking tour, the Portas do Mar plaza and carpark is a carefully considered public facility. The retention of the original stone steps at the former extent of the water’s edge, reuse of salvaged materials and detailed resolution of the carpark structure to align with the car spaces all revealed an architectural approach with care. The public space provided spaces for people to sit under the shade of trees on sunny hot days, like today. Transport values aside, it is a well-resolved public facility that demonstrates an architecture of care, whilst offering a public space with a view of the sea.

More broadly, travelling with Brad, Edwina, Ellen and Sarah, I have been challenged to reflect on what principles and values we should hold as architects in different contexts across Australia. I think Lisbon has helped to galvanise my understanding that urban settings undergo continual transformation and that architecture contributes to this. We also need to think about how we use materials ethically, and material reuse might happily imbue new meanings to existing and available resources. Lisbon’s architecture is a reminder that we can create spaces that honour layers of history, express our values and celebrate local cultures.

In several of today’s projects and the footpaths between, the local Portuguese limestone was prominent, with fossils sometimes embedded in the finished surface. I was reminded of David Farrier’s book, In Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils, which contains reflections on our anthropocentric age. After today’s walking tour, I’m reminded that architecture can contribute to the urban project of the city, and that we should consider what fossils we want to leave behind for future generations to come, as clues to what our society values the most.

– Tiffany Liew, Andrew Burns Architecture

Read more of the 2023 Dulux Study Tour Blog

Dulux Study Tour participants are invited to share their experiences in blog and editorial content as part of the program. Opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Australian Institute of Architects. The Institute encourages a space for conversation and continued dialogue so there can be meaningful change and progress across the built environment and our wider community.

2024 Dulux Study Tour – Shortlist Announced

30 emerging architects have been shortlisted for the 2024 Institute’s Dulux Study Tour. Five individuals will be selected for their contributions to architectural practice, education, design excellence and community involvement.

101 Lessons We Learned on the 2023 Dulux Study Tour

It’s been an incredible ten days, filled with visits to more than 50 buildings and meeting with approximately 20 architects across several cities: Helsinki, Lisbon, Vals/Zurich, and Venice. On our

2023 Dulux Study Tour, day 9 – Venice, four spritzes and a yarn

This year’s Venice Architecture Biennale is titled “The Laboratory of the Future” and, as set out by Biennale curator Lesley Lokko, “architects have a unique opportunity to put forward ambitious

2023 Dulux Study Tour, day 8 – Zurich: A full cup

It’s midnight in Vals – a quintessential Swiss mountain village – and you’re floating in a warm pool, looking up at the night sky, in a silent night-time bathing experience.

2023 Dulux Study Tour, Day 7 – Vals: Venerating Peter Zumthor

I remember feeling vividly – Holy shit, I won a place on this tour. I don’t know that I’ve earned this, but I’m going to embrace it. The Institute invited

2023 Dulux Study Tour, Day 6: Lisbon’s ‘foreign object’

I was pretty sure I won’t like the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT) by Amanda Levete Architects, but am trying to be open minded. A big conceptual gesture

2023 Dulux Study Tour, Day 5 – Lisbon: Beyond the fresco

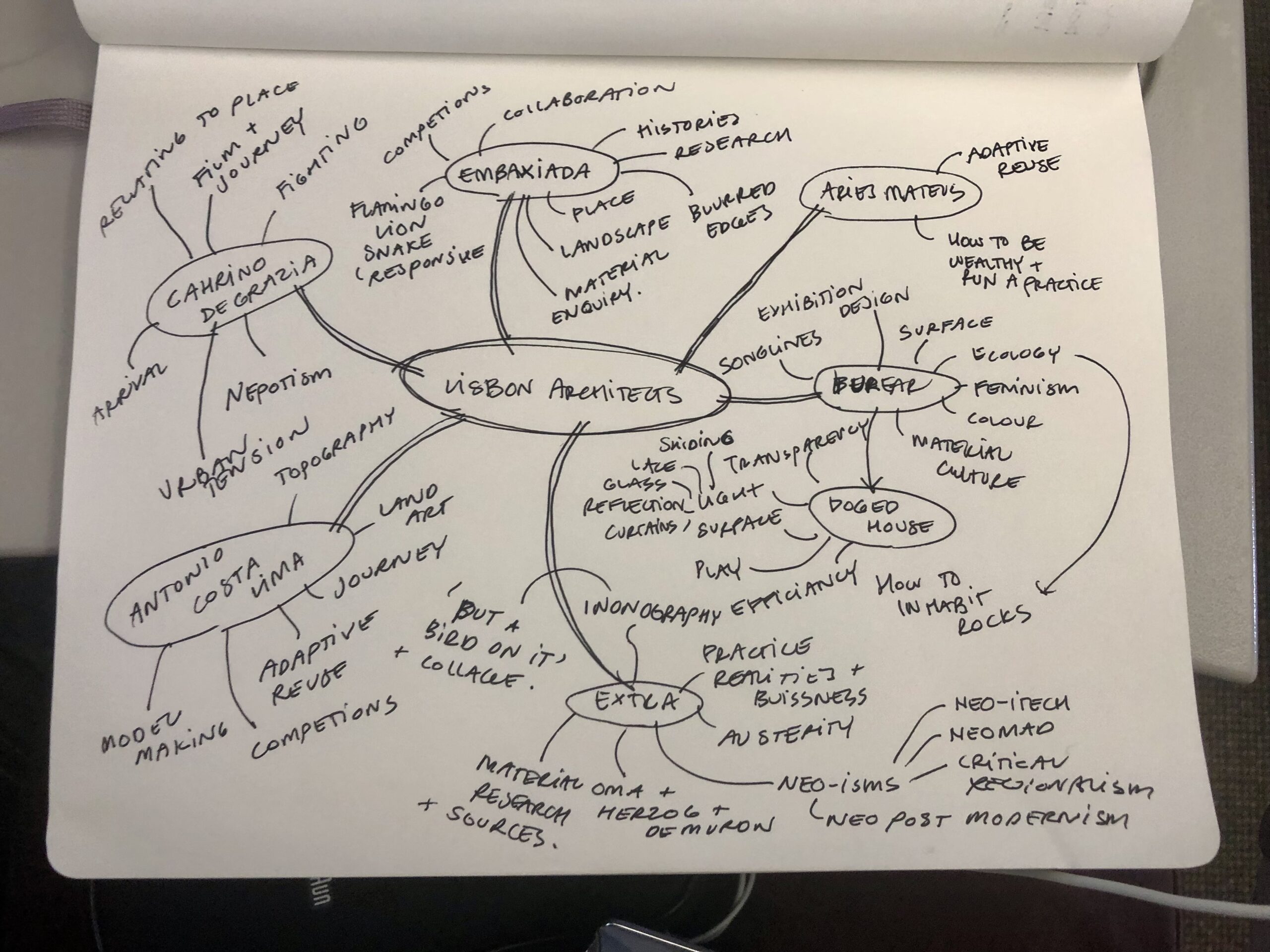

I’ve just spent the last hour and three watery coffees drawing out mind map in an attempt to untangle the many threads of thought covered yesterday. We ping-ponged across Lisbon

2023 Dulux Study Tour, day 3 – Helsinki: “Between humanism and materialism”

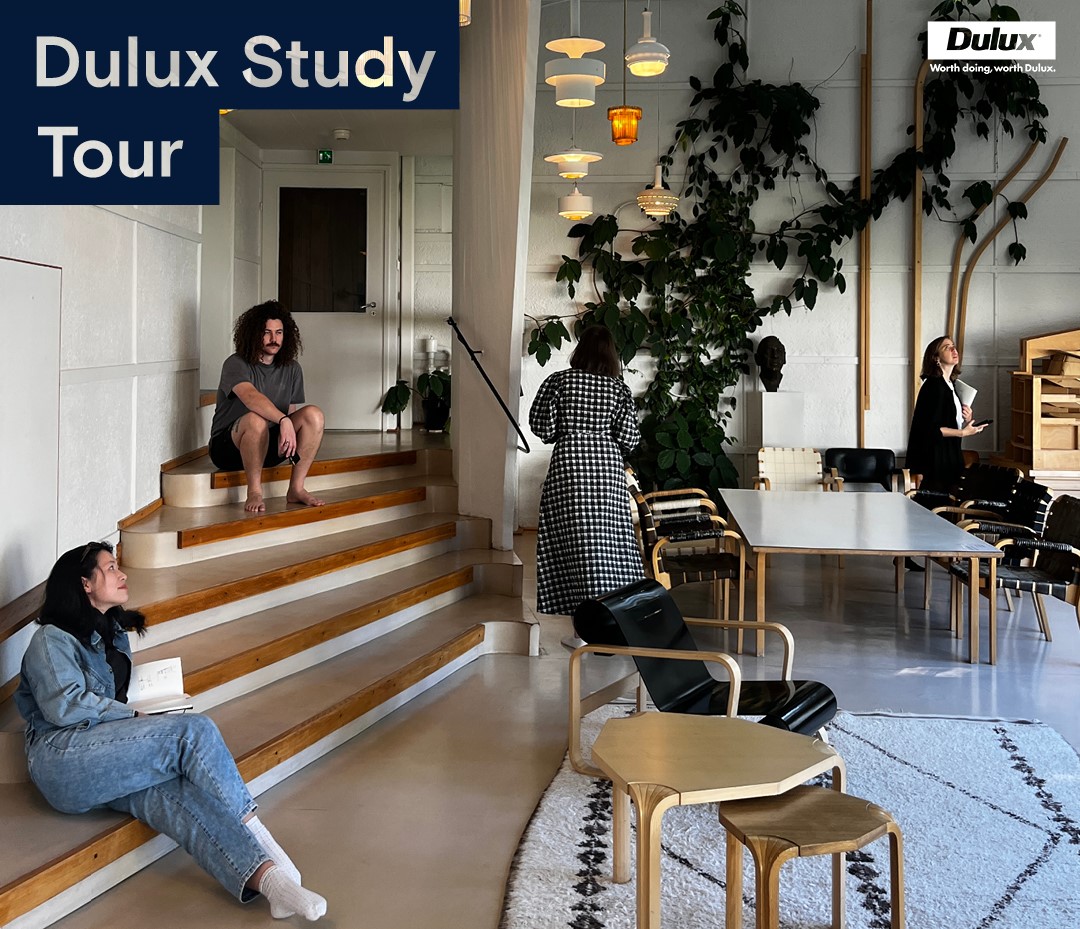

I’ve always thought that people who cried at architecture took their job way too seriously… but I must confess I had a little moment standing in the Aalto House today.

2023 Dulux Study Tour, day 2 – Helsinki: ’Sing like a choir’

Day 1, we situated ourselves in the city of Helsinki. We passed through various shades of grape, an unconscious obsession of the city, all the textures imaginable and 100 different

2023 Dulux Study Tour, day 1 – Helsinki: Architecture in Helsinki: Contact High

Finish your emails, set your out of office. Quickly flick off a fee proposal and remember to get back to Jamie about that competition entry you can’t submit. Apologise to