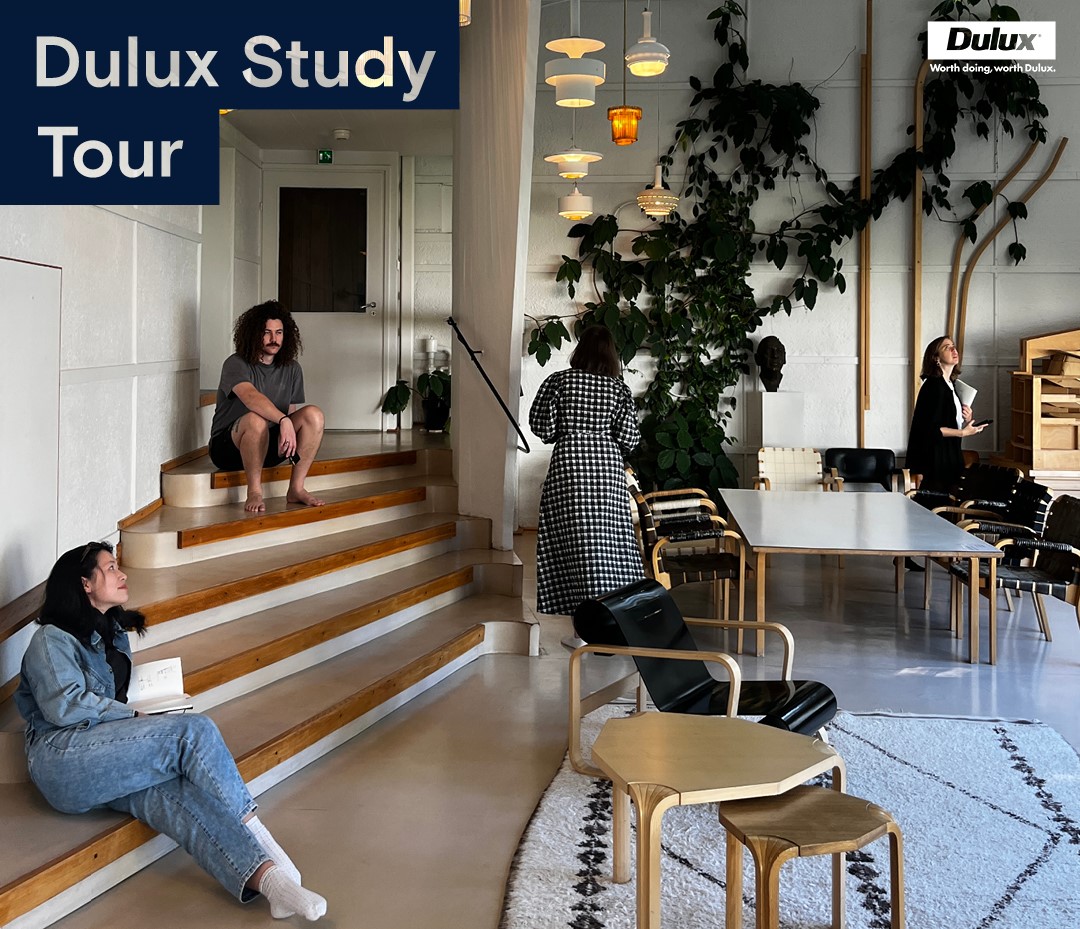

I’ve always thought that people who cried at architecture took their job way too seriously… but I must confess I had a little moment standing in the Aalto House today. I’d like to say that it was just sleep deprivation and jet lag but the privilege of the moment had me heavily swallowing some bubbling emotion. Let me explain why.

On this last day in Helsinki we visited the Aalto House and Aalto Studio. We’ve already seen many Aalto projects and they’ve transformed from buildings I vaguely remember from a history class at university to works I now have an intimate admiration for. Please note, I’ve only used the surname Aalto in this writing. This is intentional. While these works are predominantly from the skill of Alvar Aalto, there’s no doubt that credit is also due to Aino and Elissa and no doubt other integral team members at Studio Aalto.

Architecture tours usually focus on public buildings and multi-residential projects because it’s hard to visit privately owned houses, so as an architect whose work and heart lies in firmly in single homes, I was extremely excited to see the Aalto House.

I’ve seen Aalto’s work described as “between humanism and materialism” and before this trip these words felt academic and alienating to me. But having experienced these projects in three dimensions, with context and all the senses, these ‘isms’ now seem like practical and apt descriptions.

Let’s start with materialism. Helsinki is full of it. It seems to me that economic austerity during not-so-distant tough times for the country have forced Finnish designers to create texture, warmth, rational beauty and visual interest (things that humans crave) by using ordinary materials extraordinarily well. For example, brick is everywhere but it’s often laid in a unique bond; in-situ concrete is also popular but I’ve seen more timber formwork imprints than anywhere else in my life; standing seam copper and timber battening add texture and detail like threadwork on a tapestry.

And humans like this. We like detail, texture, warmth, visual interest, and a scale appropriate to our size and senses. We like the natural world and anything that reminds us of it, such as raw materials, or patterns and order that are delightfully contrasted with the ‘perfect imperfect’.

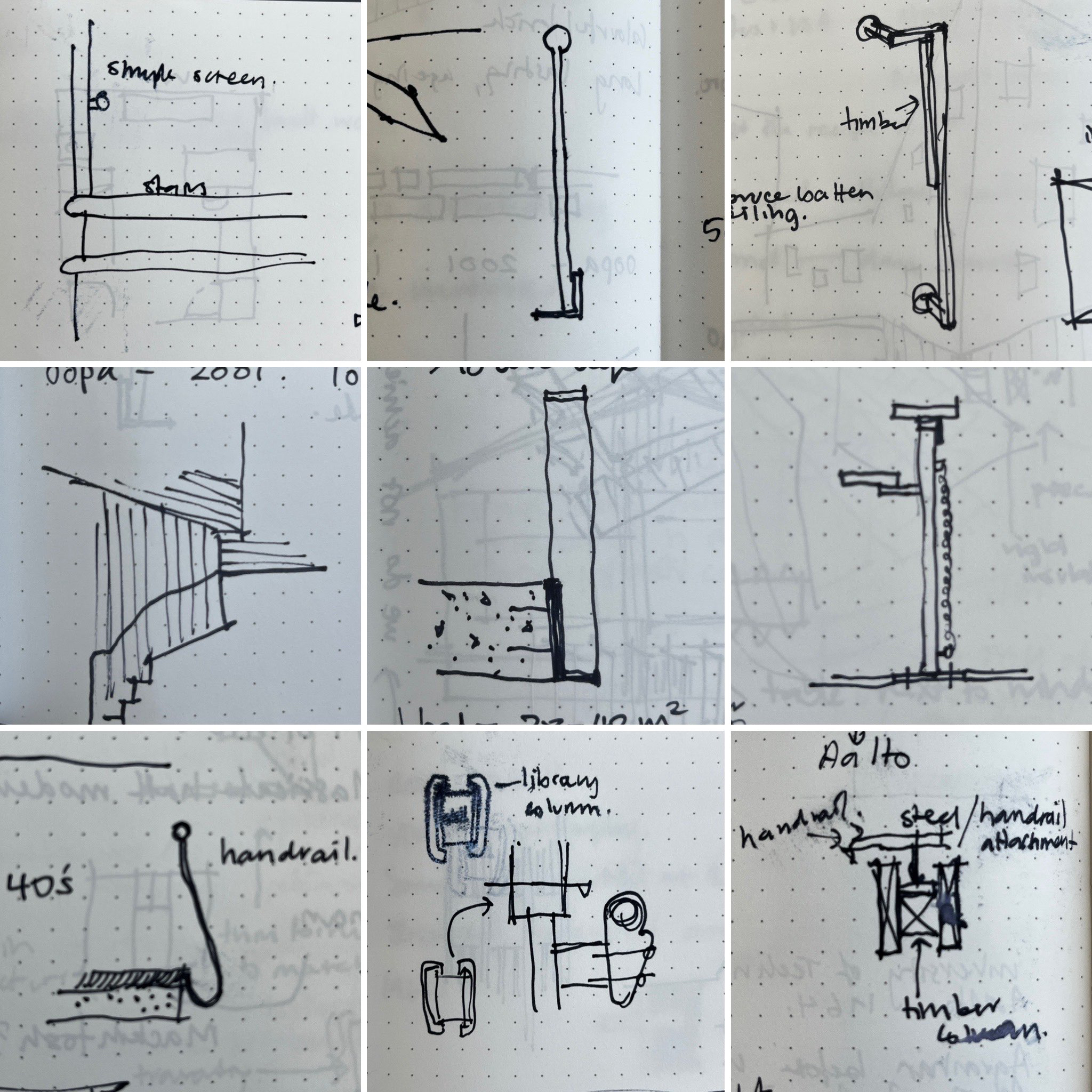

This is why Aalto’s works are particularly humanist. Aalto’s handrails and doorknobs are beautiful and ergonomic. Simple curtain dividers, woven wall panels and tensioned fabric light diffusers offer simple and delightfully textural solutions. The application of material patterns and contrasting textures offers tangible materiality, human scale, and warmth to playful volumes and modest spaces. The interest in furniture and lighting design demonstrates a near obsession with human experience and comfort. The effort to bring light into spaces in a country that suffers long dark depressing winters it generous to the inhabitants.

Am I gushing? Let me garnish with some critical thought. At both of today’s Aalto buildings I was very disappointed with the lack of physical connection to nature. The visual was there – far ahead of its time – but while Alvar Aalto had his own access to the garden, the rest of the studio had to circulate right back through a front door and walk around the building to access the primary garden spaces. And in his home, the connection to the outdoors was a little clunky. This shocked me.

And while the Aaltos didn’t have climate change on their horizon, I’m concerned for how these (and other Finnish buildings) will perform in increasingly warm summers and prolonged series of warm days. Many of their buildings have unshaded east and west windows to understandably capture as much light as possible during a typically cold climate and during short winter days. And these are buildings typically made of huge insulated thermal mass elements. This combination works well in cooler times but it can flip to a thermal nightmare when heatwaves are experienced and all that sun they’re trying to capture starts to heat and be stored in well insulated high-thermal-mass spaces. Add to this the lack of openable windows typical in cooler climate regions and I become very nervous for the future of these spaces. Maybe some of that prevalent battening needs to be repurposed into operable, optimised or removable shade screens.

And so our Helsinki whirlwind comes to an emotional end and why exactly did I feel so moved at this final site visit? Because I think I realised I was standing in pioneering proof that it was entirely possible to prioritise practicality, durability, sustainability, and modesty while achieving beauty, joy and spaces that nurtured and enriched people’s lives.

– Sarah Lebner, Cooee Architecture

Read more of the 2023 Dulux Study Tour Blog

Dulux Study Tour participants are invited to share their experiences in blog and editorial content as part of the program. Opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Australian Institute of Architects. The Institute encourages a space for conversation and continued dialogue so there can be meaningful change and progress across the built environment and our wider community.

2024 Dulux Study Tour – Shortlist Announced

30 emerging architects have been shortlisted for the 2024 Institute’s Dulux Study Tour. Five individuals will be selected for their contributions to architectural practice, education, design excellence and community involvement.

101 Lessons We Learned on the 2023 Dulux Study Tour

It’s been an incredible ten days, filled with visits to more than 50 buildings and meeting with approximately 20 architects across several cities: Helsinki, Lisbon, Vals/Zurich, and Venice. On our

2023 Dulux Study Tour, day 9 – Venice, four spritzes and a yarn

This year’s Venice Architecture Biennale is titled “The Laboratory of the Future” and, as set out by Biennale curator Lesley Lokko, “architects have a unique opportunity to put forward ambitious

2023 Dulux Study Tour, day 8 – Zurich: A full cup

It’s midnight in Vals – a quintessential Swiss mountain village – and you’re floating in a warm pool, looking up at the night sky, in a silent night-time bathing experience.

2023 Dulux Study Tour, Day 7 – Vals: Venerating Peter Zumthor

I remember feeling vividly – Holy shit, I won a place on this tour. I don’t know that I’ve earned this, but I’m going to embrace it. The Institute invited

2023 Dulux Study Tour, Day 6: Lisbon’s ‘foreign object’

I was pretty sure I won’t like the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT) by Amanda Levete Architects, but am trying to be open minded. A big conceptual gesture

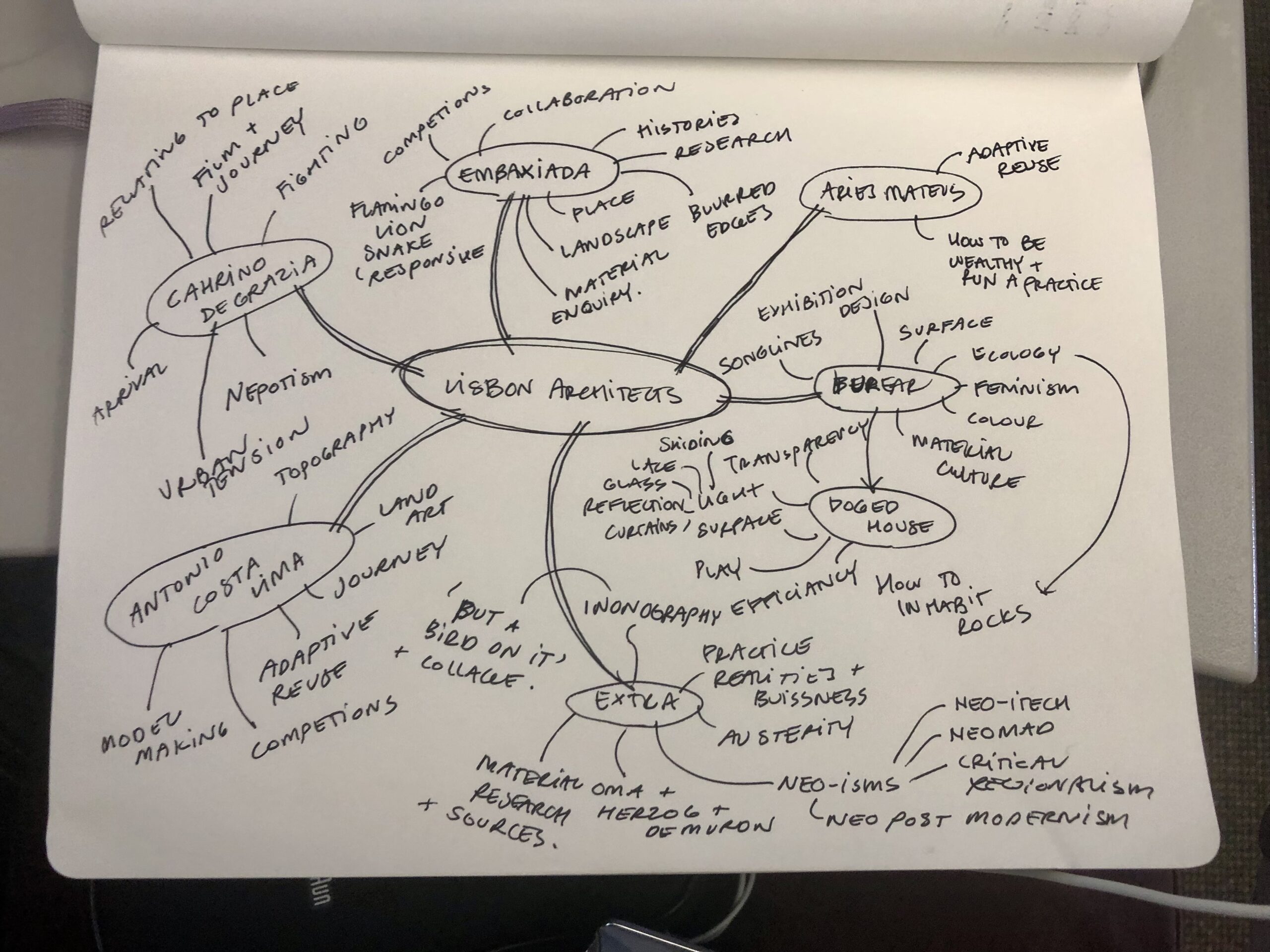

2023 Dulux Study Tour, Day 5 – Lisbon: Beyond the fresco

I’ve just spent the last hour and three watery coffees drawing out mind map in an attempt to untangle the many threads of thought covered yesterday. We ping-ponged across Lisbon

2023 Dulux Study Tour, day 4 – Lisbon: Urban Alchemy

Lisbon is a living museum – a city that reveals a rich tapestry of historical and political aspirations through its architecture. Layers of time coexist in the stratum of the

2023 Dulux Study Tour, day 2 – Helsinki: ’Sing like a choir’

Day 1, we situated ourselves in the city of Helsinki. We passed through various shades of grape, an unconscious obsession of the city, all the textures imaginable and 100 different

2023 Dulux Study Tour, day 1 – Helsinki: Architecture in Helsinki: Contact High

Finish your emails, set your out of office. Quickly flick off a fee proposal and remember to get back to Jamie about that competition entry you can’t submit. Apologise to