“Art must give suddenly, all at once, the shock of life, the sensation of breathing.” – Constantin Brancusi1

Every now and then, I see aesthetically appealing architectural projects in international professional journals. Much more rarely do I encounter projects that move me deeply, touch my entire being, and make me think about architecture from a new perspective. These rare projects are not only skilled applications of familiar approaches; they convey a deeper understanding of architecture and its human calling. They open up different, poetic views to human existence by making us see, feel and think about our being in the world with a new sensitivity and understanding. These projects and buildings often disturb our established views of the means and meanings of the art of construction.

Seeing photographs of Richard Leplastrier’s Northern Beaches Palm Garden House (1974–76), and later visiting it, was just such a reorienting experience for me. It was not only the disciplinary and artistic quality of its architecture that stunned me, but Leplastrier’s entire attitude to life and apparent fusion of the house with its natural environment. Large lizards lived around and in the house like domestic animals, suggesting a paradise, or a way of living in harmony with nature.

Similarly, photographs of Glenn Murcutt’s Marie Short House (1974–75/1980) in Kempsey added an entirely new dimension. Years later, I spent a few days in the house, surrounded by open agricultural land and droves of kangaroos. The site spoke of long farming traditions and a way of living that widened into the landscape. The architecture itself echoed the matter-of-factness of traditional farm structures, equipment and tools, yet it projected a refined and lively sense of function and beauty. The categories of new and traditional, regional and universal, usefulness and pleasure, were fused.

Both these Australian houses questioned the established reading of architectural history, as well as a narrow notion of modernity. All truly creative works contain disturbing dimensions; this feeling of uneasiness arises from the shaking of the foundations of convention. The first performance of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris in 1913 caused a street riot.

Images of Sean Godsell’s early houses, shown in his lecture at the Alvar Aalto Symposium in Finland in 2006,2 also impressed and disturbed me at the same time. These houses were forcefully beyond aesthetics; they projected muscular and tactile experiences and also suggested a new existential perspective. The regular structural frames and the rational organization of the various acts of dwelling within their volumes were familiar to me from the iconic houses of Mies van der Rohe, as well as the Case Study Houses of California in the 1940s to ’60s by a number of younger American architects.3 The numerous elegant and optimistic modernist houses commissioned by the Arts & Architecture journal could well be the high point in the history of modern house design. There was also a parallel constructivist orientation in Finland during the 1960s – a movement with which I was personally involved – focused on timber construction.

Godsell’s projects could be categorized as rationalist, constructivist or minimalist, but they appear as manifestos of something new; they were absolutely determined, unapologetic, tough and elegant, all at the same time. Their rectangular geometry was often articulated and enriched by warmly coloured wood lattices, giving an elegant, translucent and tactile quality – almost like a textile, of sorts. One could almost see into the spaces through these lattice surfaces, and the life behind the screens appeared unconstrained and inviting.

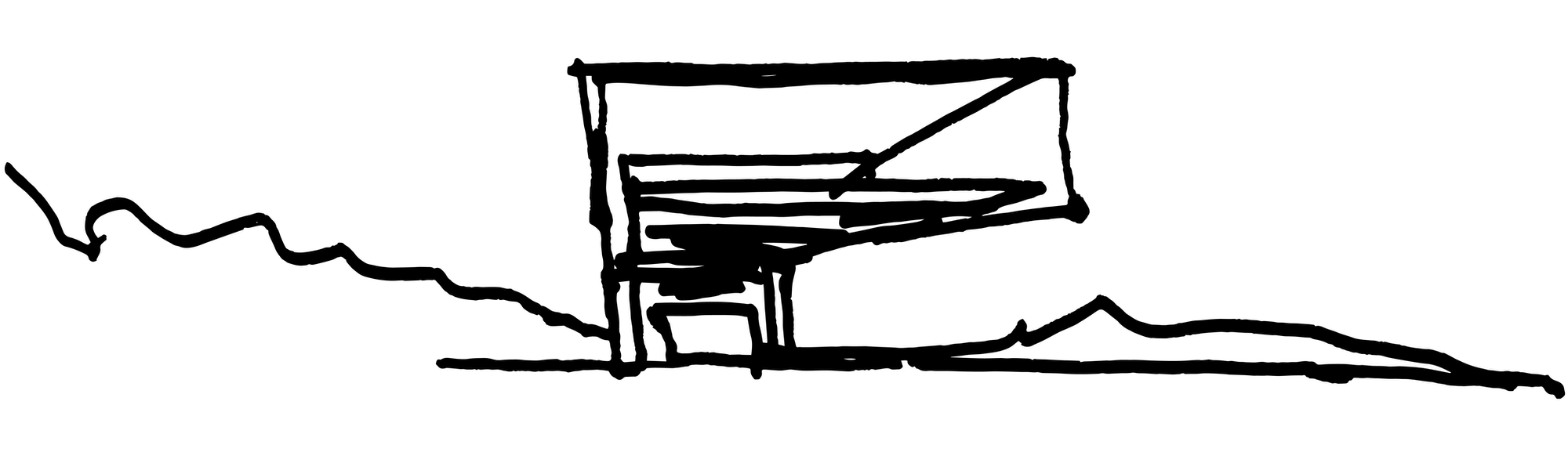

At the same time that Godsell’s houses were lifted above the ground, they had a rigorous relationship with earth, landscape, horizon, climate and sky. The perfected buildings seemed to underline and orchestrate the subtleties, textures, colours and even odours of the setting. In some cases, the house appeared as a mere line across the undulating terrain, or a single rectangular volume in the landscape. These houses were not just isolated objects; they were part of the very character or their setting, and in a dialectic relation and conversation with it. The strictly organized structural frame of red-brown Corten steel continued the structural thinking that I knew, but the combination of utter simplicity and the concealed views behind the lattice screens evoked subtle invitations. These houses were not just skillfully executed constructions; they created entire worlds, fused with and in dialogue with their settings. In fact, these houses were devices and instruments for reading the nuances and subtleties of the landscape and the weather. They concretized French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s memorable formulation of artistic inclusivity: “We come to see not the work of art, but the world according to the work.”4

This architecture could hardly exist anywhere else, as the wide and borderless landscape with high sky and impressive vegetation and animals hardly exists elsewhere. I sensed something authentically Australian in this counterpoint of dwelling and landscape. In fact, this fusion applies to all authentic works of art; they are not isolated objects, they are poetic realities and complete microcosmic worlds. Andrey Tarkovsky, one of the finest film directors of all time, expresses the idea of artistic inclusivity succinctly: “The artistic image is not a specific meaning … but the entire world is reflected in it as in a drop of water.”5 Meaningful works of art are constantly open to interaction and dialogue with other works, even on the reverse side of the globe and through centuries of time. They converse eagerly and remind us of other works and suggest new relationships and influences.

Godsell’s work is grounded in a thorough and internalized knowledge of the arts, and his process of condensation echoes the thinking in modern art from cubism to abstract expressionism and land art. I can sense the black and white squares of Kazimir Malevich, the condensed minimalism of Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt, and the landscape projects of Michael Heizer and Walter de Maria, as well as the cosmic light works of James Turrell in conversation with Godsell’s architecture. Simply, all meaningful art is bravely inclusive, not timidly exclusive and defensive.

The elegant and rough materiality, as well as the simplicity, of Godsell’s plans are in a convincing dialogue with the vastness and toughness of the Australian landscape. The persistence of this architecture made me think of the Indigenous history and the pioneer settlements of Australia. The architect himself uses the notion of “bush mechanic” in reference to the straightforwardness of his approach to technical issues. Even in their simplicity and silence, these houses project an epic narrative. It is this epic width and depth that seems to be disappearing in most of today’s celebrated architecture, while the narrow and stylistic understanding of abstraction and minimalism erases the dialogical and existential meanings.

Godsell has also applied his minimalist but empathic line outside of the privileged, well-to-do clients. His Bus Shelter House, Future Shack and Park Bench House are habitable street furniture for the homeless, while the Bugiga Hiker Camp is a shelter for long-distance walkers. He has even expanded his line of functionalized and movable devices to spiritual structures in the Vatican Chapel at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale; with the interior of its prefabricated tower coloured golden yellow, it offers a device to experience the silencing depth of the sky.

“Simplicity is not an end in art, but one arrives at simplicity in spite of oneself, in approaching the real essence of things … simplicity is at bottom complexity and one must be nourished on its essence to understand its significance,” advises Constantin Brancusi, the master of lifelike simplicity.6 Artistic simplicity is not reduction or subtraction, it is a compression of observations, experiences, qualities, intentions and meanings into a formally simple entity. Reductive simplicity in itself is not a quality in art; only simplicity that arises from and results in processes of compressing and fusing content is meaningful.

Sean Godsell has continued firmly his process of compressing form and meaning, and his later projects contain nearly nothing, but yet, everything is there. His House in the Hills is simply a constructed and adjustable shadow, but it ties back to timeless traditions of resting in the shade of a large tree, the man-made shelters of Indigenous builders, and the fundamental human need for finding shelter and making an experiential place. Godsell tested the idea of total flexibility in the glass-covered MPavilion, which could be opened up on all of its five sides. His RMIT Design Hub in Melbourne appears as a single minimal volume, covered by countless movable circular facade elements, but it reacts sensitively to climate and light and provides spaces for demanding research work. This project could even be seen as organic architecture, not in terms of form, but in its very principle of adjusting to the prevailing environmental conditions. Its rectangular appearance does not intentionally reveal or celebrate the technical, functional and experiential complexities of the interior spaces.

Sean and I have been friends since our first encounter in the Nordic summer in 2006, and I have learned to value his directness, reliability, energy and ever-supportive attitude. His compressed aesthetics is also his way of life and he fuses his aesthetic ideals with an ethical stance. As the practice of architecture is increasingly turning into a professional service, we are in great need of architects who do not run their practice as a business, but who practise an ethical craft and follow a personal calling with the intention of dignifying human life.

Notes

- Eric Shanes, Constantin Brancusi (Modern Masters Series) (New York: Abbeville Press, 1989), 67.

- Godsell gave a lecture entitled “Regional Realities” at the 2006 Alvar Aalto Symposium, which had the general title Less and More.

- Elizabeth A. T. Smith, Case Study Houses (Cologne: Taschen, 2008).

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, as quoted in Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 184.

- Andrey Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema (London: The Bodley Head Ltd., 1986), 100.

- Constantin Brancusi, Brancusi Exhibition November 17–December 15, 1926 (New York: Brummer Gallery, 1926).

Juhani Pallasmaa is an architect, professor emeritus and writer based in Helsinki.