Indigenizing practice: Country and architectural pedagogy

In teaching architecture students at the University of Sydney School of Architecture, Michael Mossman, Associate Dean Indigenous, instils a dynamic design process that is situated within the presence of Country, and in continual dialogue and exchange with it.

Country is the realm that surrounds us all, with different understandings immanent in each of us. As a Kuku-Yalanji man, partner, father, son and brother who grew up in Gimuy1 on Yidinji land and now lives and works on Gadigal land, I am always Country and I am always part of Country – Country is always me and Country is always part of me. I am my story – my Country, my culture and my community – and it is always evolving. As an educator in architecture and the Associate Dean Indigenous at the University of Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning, these fundamental understandings underpin my pedagogical approach and centre its empowerment of relationships, collaboration, yarning my story and listening to others yarn their stories.

Constitutive of everything, Country is everywhere and always and subjectively relational to living beings. I introduce myself as Kuku-Yalanji; I am-Kuku Yalanji and Kuku-Yalanji constitutes me. Furthermore, I play a part in a storyline of a broader narrative alongside every other actor around me. Country is infinite and a process of the way I constantly relate to Her. It is the process before thought – becoming from within, extended outwards and reciprocated back. Applied to all beings, a continual exchange is always occurring – a Third Space.2 As a result, Country possesses definitions and values that are moving, never static, always produced and never-ending.

During the final stages of my doctorate studies, I encountered Spinoza’s seventeenth-century philosophical concept of Nature and God that reconciled the notion of one substance and the terms natura naturata and natura naturans – the former meaning that we are “natured nature” (in the sense that we have always been) and the latter “naturing nature” (our actions mean that we are always becoming, relative to all other beings “naturing”).3 On this continent, placemaking has always been, and is always becoming, Country or Nature/God, in deeply connected relationships with all beings.

Architecture, in the built environment sense, can understand this notion to meaningfully connect with Country, with Her infinite attributes. Connecting with Country in a culturally competent sense, through memories of place and associated activities, produces ever-changing concepts of the past, dependent on my lens in the moment. I can also envision possibilities to activate and interact with concepts of the future. What has been and what is becoming is always in flux.

I acknowledge Country as the presence in which architecture is situated, and with which it engages in continual dialogue and exchange. As in the “rhizome” described by Deleuze and Guattari in their 1980 book A Thousand Plateaus,4 situatedness is relational to place and all its connected beings that enact infinitely interacting networks of evolving thought.

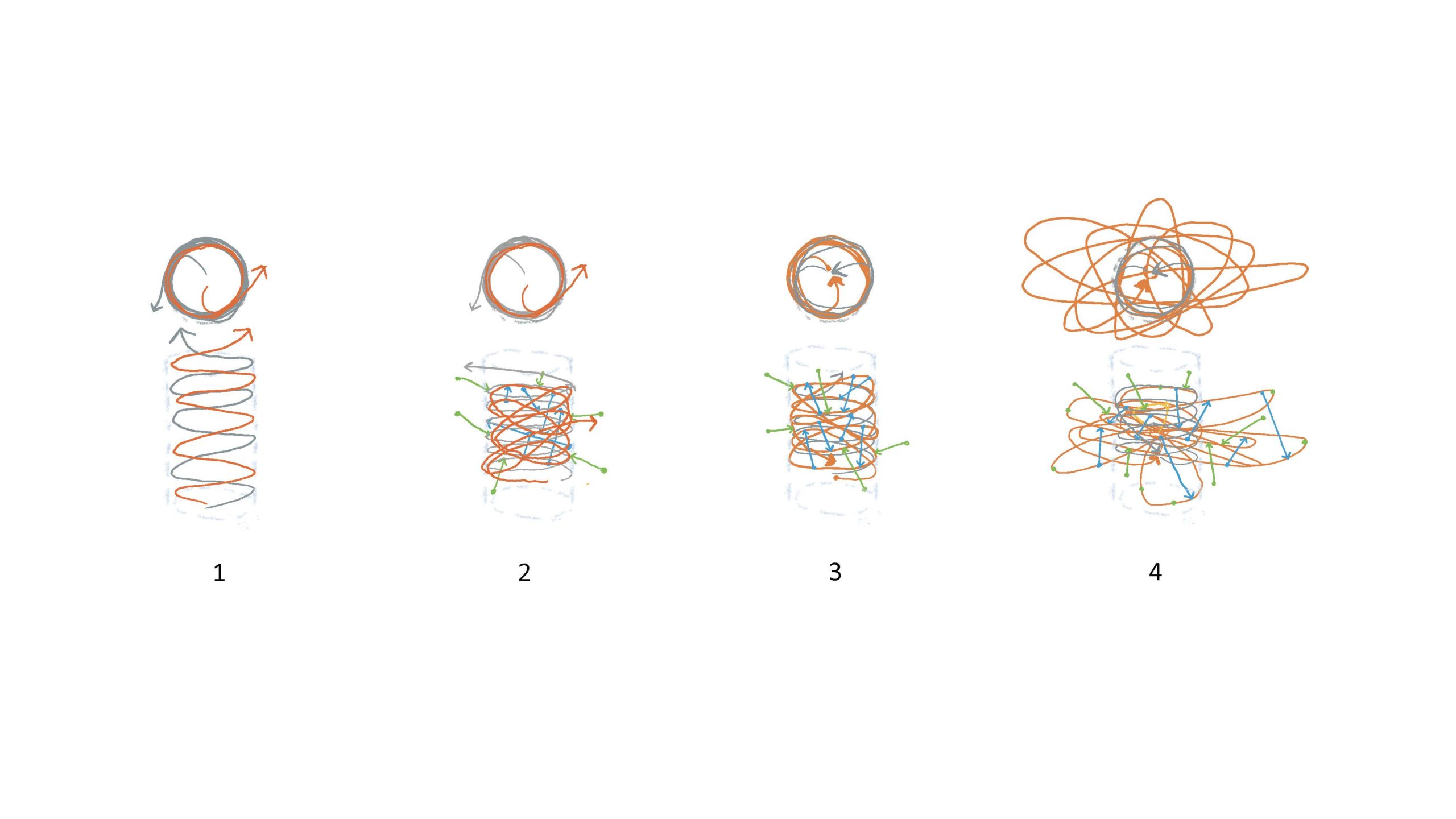

The scale of these connections is commensurable with the relationships established in the formation of collaborative and co-designed ways. If relationships are present, reciprocal and strong, the translation of ways received through a Third Space presents opportunities for dynamic design processes. Ultimately, I can never fully know what is not meant to be known; however, I can create concepts relational to my encounters and present an architectural process that is more than linear with an end. Rather, it is networked, connecting in different ways from within oneself, reaching out in all directions to exchange information, returning on oneself.

Occurring prior to concept creation, thought from within is projected out to the infiniteness of Country to ultimately return with exchanged information. I do not wait for knowledge to come to me; my thought meets the knowledge somewhere in between, in a Third Space. Architecture does the same by possessing concepts from the mind of the architect, from the storylines of the materials, and from the DNA presence of those who interacted with – and continue to interact with – the place. That presence is embedded forever and is always giving and receiving, always creating concepts through new exchanges. Always Country.

From the Heart

This year, I taught an architecture master’s studio at the University of Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning. Called “From the Heart,” it involved exchange within the infinity of Country, where there are boundless causes and effects, a multitude of means to a continuum of ends, endless rationalities to theorize and unfathomable experiences to acquire and understand. “From the Heart” is an iterative process that starts from within oneself, reaches out to the infiniteness of Country and returns to oneself with exchanged information.

The logic of inquiry is rhizomatic, whereby an architectural process, in the moments of concept creation, is always subjectively relational between beings and can present anywhere and at any time. The immersiveness of the “From the Heart” architecture studio was speculative to create relationships and exchanges in those fleeting moments for application to that specific place. After that moment, we were always in a different place and time and the exercise process continually circled around to effect a continuously dynamic design process. These relationships will now last a lifetime.

Situated in Sydney’s Redfern, near The Block, “From the Heart” worked with Shane Phillips from the Koori Lighthouse Youth Organisation. The studio developed a former textiles factory and community place into medium-density mixed-use and affordable accommodation – inclusive and celebratory of Country and local cultures. It was informed by Shane’s initial working relationship with Cracknell and Lonergan Architects, the Uluru Statement from the Heart’s key themes of Voice, Treaty and Truth, and The Makarrata Project album by Midnight Oil.

Shane communicated to the students that they would become part of the DNA of the project from the moment they commenced their involvement; this provided a foundation to interweave understandings of Country and cultural significance into the project, encouraging students to reach out to the infinite to inform their architectural responses.

The first task is always to walk Country – to move out of the studio and feel Her presence. Our walk to Redfern from the Darlington campus meant that we connected with Country. Shane’s wise words of place, cultural exchange and community aspiration provided the human connection to Country and the inspiration for the students to interact wholeheartedly with the studio exercise.

This interaction zone is the Third Space, the in-between that is the continuum of exchange in evolving and relational settings. When architecture is conceived as the mindset of the individual and the individual is Country or nature, the creative expression of the built form is Country. For this exceptional group of masters’ students, their mindsets were open to the interactions and processes of exchange constitutive of Country.

The 14-week process resulted in conversations in relation to the architecture and its context, podcast yarns and questions such as “What is Country?” and “What do the Uluru Statement’s key principles of Voice, Treaty and Truth mean to you?” We learned from each other and applied these expressions relative to the architectural design process to produce amazing submissions. Connection to Country means connecting principles, experiences, memories, rationales and processes. I extended these concepts to the students to challenge norms and received profound responses that in turn inspired me to push myself further in this studio and for the next one. This is a conversation that I will give to anyone who would like to receive.

Yarning circles

The “yarning circle” is a dialogical space for meaningful conversations. The school has commenced the Architecture, Design and Planning (ADP) Yarning Circles to facilitate important First Nations conversations. The invitation is for everyone to attend, listen, participate and contribute notes on the interactive board. These are important dialogues so academic and professional staff, students, alumni and friends are welcome to engage with a key topic for the month, present truths, and see and listen to the truths of others.

With lecturers Clare Cooper and Elle Davidson, we ask key questions at the beginning of each yarn: “What’s your Country and cultures? Who’s your family? And tell us about yourself?” The yarning circle is a space to get together and learn about each other, personally, culturally, professionally and spiritually. It’s a space to break down Westernized silos and do business in a safe, collaborative way. The circle is open to all as a method of learning about First Nations ways and making connections between architecture and Country, Cultures and Communities. It is a chance to allow yourself to become vulnerable and to engage with the deep-time significance of Country and your connections to the important places of your own ancestry.

Our most recent yarning circle asked: “What does the Uluru Statement mean to the ADP school?” This will form the basis of a number of future yarning circles that will interrogate the notion, and other similar issues, to include as many voices as possible. The circle is a place of interaction, exchange and transformation of information, giving architecture schools the chance to learn about and better understand First Nations issues. In this environment, I learn about my colleagues and friends in deeper ways. We all learn about each other, and I thoroughly recommend that all schools and practices carry out the same process.

On this continent, Country and our First Nations cultures are distinct and have the potential to deeply enrich our architectural practices and the process we undertake to arrive at a physical manifestation of our thoughts. I work in an educational environment to give my knowledge and insights to the next generations of architectural practitioners and to current academics and researchers. There is a level of satisfaction in knowing that these yarning circles have an impact on ways of thinking in architecture relative to practice, curriculum, pedagogy and research domains.

Our futures

The 2021 National Standard of Competency for Architects5 includes Country and First Nations principles in all phases of a project and requires education, registration and continuing practice application to provide evidence of the implementation of principles. I approach these principles through culturally and morally competent practices within educational institutions, such as the “From the Heart” studio and the ADP Yarning Circles, to create relational and interactive journeys for us all. Yes – there are unknowns; not everything is meant to be known. But we are meant to learn as much as we can to build capacities that reach out to Country and understand our role within Her realm. By creating relationships and spaces of exchange, we can reach out together to connect with Country and relate to, understand and appreciate something about each other along the way.

Notes

- Gimuy is the traditional place name for the area now occupied by Cairns in Far North Queensland.

- The Third Space theory, which explains the evolving space between interacting beings and cultures that results in new ways, is attributed to Homi K. Bhabha.

- Benedictus de Spinoza, Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Order (1677), Part 1, Proposition 29.

- Gilles Deleuze and Feliz Guattari (transl. Brian Massumi), A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), Chapter 1.

- The 2021 Standard (released on 1 July 2021, active from 2022), available on the Architects Accreditation Council of Australia website (aaca.org.au), is a credit to the work of the Australian Institute of Architects’ First Nations Advisory Working Group and Cultural Reference Panel.

Michael Mossman is a Kuku Yalanji man, born and raised in Cairns on Yidinji Country. He is a lecturer and researcher at the University of Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning. He is an architect (non-practising) and an advocate for structural change in architecture at educational, practice and policy levels.