Material specificity: A “radically conservative” approach

As a transformative profession, architecture inevitably impacts the Country whose materials it consumes. By grounding design processes in Country and embracing the nuances of place, we can achieve fit-for-purpose built outcomes that could exist nowhere else, explains Michael McMahon.

What does it mean to design and build on unceded, First Nations land? This question prompts us to reflect on where we’re at as an industry and to begin the dialogue required to understand whose Country we are on. Examining business-as-usual practices and grounding design processes in Country are important steps in moving towards a more equitable built environment. We are always on someone’s Country, and where we are geographically is where we are culturally.

What is material specificity?

The stranger is much struck by the handsome appearance given by the profuse use of cedar in the fittings of the Sydney dwellings. — Lieutenant-colonel Godfrey Mundy, 1848

On 22 February 2022, Lismore and the greater Northern Rivers region of New South Wales – Bundjalung Country – experienced the worst flood event in Australia’s modern history. The cultural, social, economic and emotional cost was – and remains – immense.

As I helped my family clean up after the flood, various questions ran through my mind – in particular, how did Lismore come to be built on a floodplain on the banks of the Wilsons River? The city sits at the eastern extent of what was once Australia’s largest area of lowland subtropical rainforest, known colloquially as the Big Scrub. From the 1840s, timber cutters moved west from Ballina, felling as they went. Their primary interest was Australian red cedar (Toona ciliata), known locally as “Red Gold.” Highly prized for its appearance, ease of handling and pest resistance, red cedar was used to build ships, furnish houses, decorate churches, dignify town halls, and make banks and boardrooms grandiose in colonial Australia. Also exported throughout the Commonwealth, it became one of Australia’s largest industries in terms of both the revenue it generated and its impact on the built and grown environments. By the beginning of the twentieth century, red cedar had been cut to commercial extinction. Along with the red cedar exported from Bundjalung Country went the sites of significance, economies and communities that depended on this previously rich and diverse environment.

Considering Lismore, which is connected to various locations through materials sourced from Bundjalung Country, it is clear that the choice of materials we use to make our buildings has a direct effect on the environment, culture, economies and communities from which those materials come. All materials come from Country, and all materials will return to Country. To make material choices that support and repair Country, as opposed to exploiting and destroying it, we need to develop a more thorough and nuanced understanding of how materials relate to site – whether this relationship is one of construction or extraction. We must strive for material specificity – that is, the use of materials that belong or relate uniquely to a particular site.

Materials custodians

Recognizing that the materials we build with have an impact on Country highlights the agency and responsibility we have as architects. Our material choices reflect what we value. Do we want to repair, strengthen and engage with community, custodians and Country, or do we want to take, pollute and destroy? Architecture is transformative in nature and there will always be a level of consumption and extraction associated with building. However, there are processes, methodologies and approaches that we can practise to support notions of care in our built and grown environments.

In 2020, the Foundation for Indigenous Sustainable Health (FISH) and the Aboriginal community of Bawoorrooga constructed the Bawoorrooga Super Adobe Earthhouse (2020) from the red earth of Gooniyandi Country in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. The project aimed to be “a national prototype for sustainable Indigenous community ownership, training, employment, housing and enterprise development.” This included the introduction of new ways of working with materials, from design to set-up.

Material specificity results in built outcomes that cannot exist anywhere else. The approach includes fit-for-purpose solutions to problems that are understood by the community. Assemble and BC Architects renovated a nineteenth-century train depot in Arles, France, to provide a new workspace for Atelier Luma, a circular-design and biomaterials laboratory. The project, completed in 2023, demonstrates a new attitude toward materiality that facilitates the ambitions of the lab. The result is an architecture that is highly specific to its place and that promotes bioregional design practice.

One way to design with Country is to reuse materials. By valuing an existing material as a resource, rather than regarding it as waste, we avoid the extraction and consumption that comes with sourcing and manufacturing new materials. The question here is: Do we need to build new in order to meet the brief? For their Mode and Design (MAD) Brussels project (2017), Rotor and Vplus developed a process that they describe as “radically conservative.” The project – the transformation of an existing office and warehouse complex in Brussels for a design and fashion centre – sought to preserve the building volumes and make use of as much as possible of what was already there. This high level of tolerance toward the existing conditions, and consideration of new additions in the context of what already existed, resulted in a reduction of new materials used alongside a richness of spatial configuration and materials that could not be realized with a new build. The reuse of materials reframes the client as the custodian of a set of building materials.

Material specificity on the ground

Where to from here? We move forward by asking where we are and what we are doing. By grounding ourselves in Country and practising with responsibility, accountability and care. By working toward a deeper understanding and appreciation of our materials. Material specificity will encourage informed, collaborative responses to problems that are underpinned by environmental awareness.

What does material specificity look like on the ground? It is important to engage knowledge holders in matters that relate to their Country. Effective engagement is a sustained process that provides Traditional Custodians with the opportunity to actively participate in decision-making. Before you approach the Traditional Custodians, do some research so that you’re not going to them with questions, but for decisions. The following questions are a to guide thinking about material specificity:

Whose country I am on?

What material cultures exist here?

How have material cultures been practised in the past, how are they practised now and how might they be practised in the future? (Culture and how people engage with materials is constantly evolving.)

What skill sets exist in the community and how can knowledge-holders be engaged in the design process to recognize existing skill sets and develop new ones?

Is building new appropriate?

What materials can be engaged with and how can we do this in an appropriate way?

Where has the chosen material come from and what is its life cycle?

Will we return materials to Country as a resource or as waste?

Guided by the Country we are on, we can develop appropriate modes of practice that embrace the nuances of place.

First Nations leader at Wardle Michael McMahon completed a master’s of architecture in 2020 at the Royal College of Art in London as a Roberta Sykes Scholar. More recently, he has been appointed to the Heritage Council of Victoria.

Published online:

04 Mar 2024

Source:

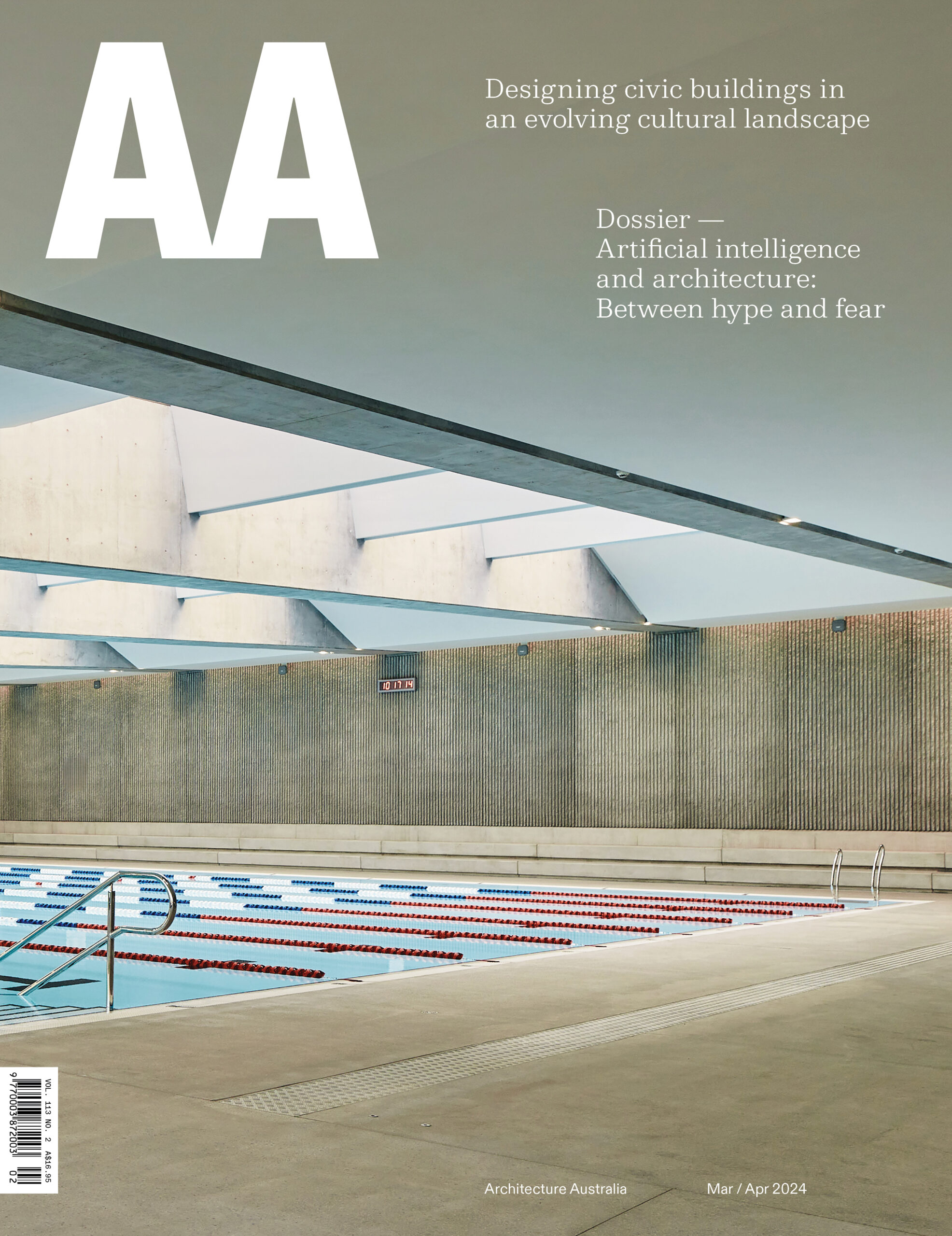

Designing civic buildings in an evolving cultural landscape

Mar / Apr

2024