Climate change and the architectural profession

Parts of this article are drawn from the Co-ordinated Climate Action Plan (C-Cap) report to National Council of the Australian Institute of Architects by Donaldson, Brogden, McLeod and Holland on behalf of CAST (the Instituteʼs Climate Action and Sustainability Taskforce), recommending the Institute adopt the target of 2030 for decarbonising the Australian Construction Industry. This target was endorsed by National Council in November 2020.

One of the key aspects of elevating the conversation from sustainability to climate change is to shift the thinking from what is feasible to what is necessary to avoid catastrophic changes to the environment.

The 2021 IPCC report and COP26 both illustrate that it may soon be too late. Even among past sceptics, there is now widespread admission that climate change is already happening. But there remains an implicit on-going denial of the science which predicted climate change. By not acknowledging that the science is clearly telling us of the immediacy of the crisis – that the focus should be on 2030 for the fundamental shifts necessary rather than the more nebulous target of 2050 – this leads to unfounded optimism that industry will deliver the solution.

We need major reductions in carbon emissions by 2030 and right now the trend has shifted in the wrong direction.

So what are the extreme risks identified by the current science?

Heiss Zeit, German 2018 word of the year, meaning hothouse earth.

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released the Global Warming of 1.5°C report, which stated that “there is no documented historic precedent” for the scale of changes necessary to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Known for its conservative climate change modelling, IPCC projections have been consistently exceeded since the first assessment report in 1990. Based on the most recent predictions from the IPCC, if levels continue to rise at the current rate, 91 scientists and policy experts from 44 countries agreed with high confidence that global warming is likely to reach 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052. In fact, the World Meteorological Organisation has warned that this limit may be temporarily exceeded as early as 2024 due to an El Niño weather pattern (Canadell & Jackson, 2020).

The questions around climate change no longer centre on whether impacts will be felt, but rather, how extreme those impacts will be. The Global Warming of 1.5°C has an arresting undertone of urgency in the authors’ insistence of real and significant threats faced. It highlights that – even if we enact immediate change – we face significant disruption.

There is an increasingly compelling body of evidence that the timeline for decarbonising the economy is required in advance of the much-discussed target of 2050 and this was stated with even greater urgency in the 2021 IPCC report. Research published by the Potsdam Institute argues the absolute imperative for action to decarbonise the global economy in the next 10 to 20 years (Steffen, 2018). A lesser target cannot be contemplated.

In the last 2.5 to 3 million years (the Pleistocene), when the earth looked roughly like it does now, the earth’s temperature never exceeded that of the pre-industrial period by 2°C, despite all major disruptions over this time. The earth has managed to regulate the impact of greenhouse gases naturally within a very narrow band of variance. That is, up until now.

After 150 years we are at risk of destroying that balance permanently. The earth is warming at 170 times faster than in the previous 7000 years of the Holocene interglacial period. The Potsdam work indicates that a 2°C increase (today at 1.2°C) risks being the tipping point with a potential shift from a self-cooling mechanism to an unstoppable and irreversible selfheating system and a pathway to Heiss Zeit (hothouse earth), where the temperature is between 4°C to 8°C higher and oceans are 10 to 60m higher, rendering much of the earth uninhabitable.

Clearly this is a risk we cannot contemplate.

National Construction Code

Given the construction industry is responsible for nearly 40% of emissions, it is a prime target for getting on track to a zero carbon economy.

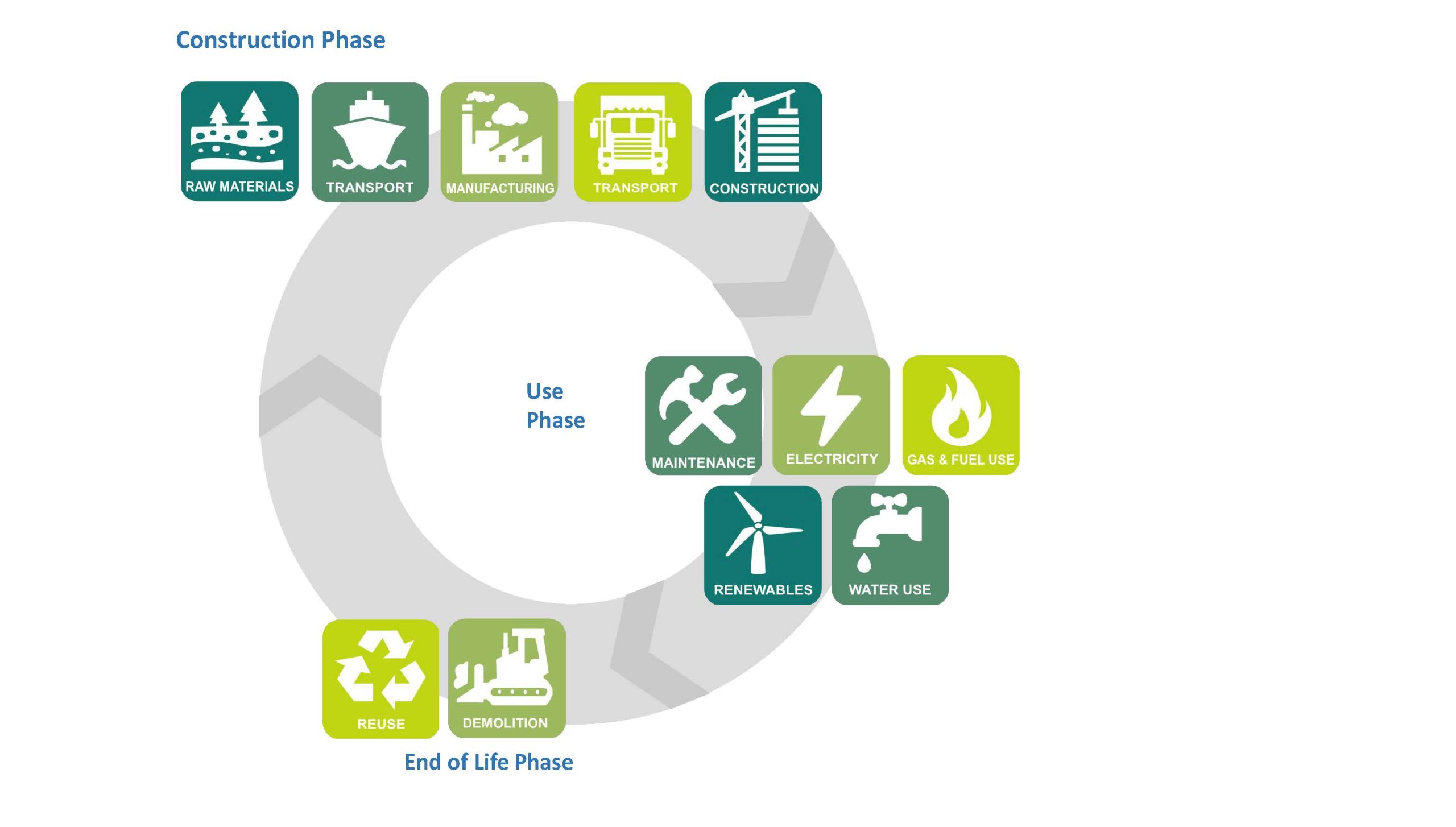

Carbon emissions occur across:

- the carbon embodied in the manufacture of the materials used in their construction

- the transport of materials to site

- the energy used in construction

- the energy consumed in the operation of buildings across their lifecycle

- the energy and carbon associated with their end of life (and hopefully extending its life through its repurposing rather than demolition).

The urgency requires that the changes cannot be left to individual initiatives to decarbonise. The necessary pace of change requires regulatory assistance. A key part of the regulatory pathway to zero carbon will be the National Construction Code (NCC) moving towards limiting operational and embodied carbon in all buildings. This should address whole of life carbon – all carbon generated across the lifecycle of a building.

Life Cycle Assessment

The construction industry offers the opportunity for moving more rapidly than other elements of the economy. In considering the pathway for managing carbon in the construction industry downwards, measuring the current performance of buildings is crucial. Measuring the whole of life carbon is called Life Cycle Assessment (LCA).

To capitalise on this opportunity in a feasible and equitable way, we need to make some quick advances in building the practice across the industry for measuring whole of life carbon, including LCA modelling at the design stage.

In the United Kingdom, the Building Regulations (2010) last year released its Part Z, mandating LCA reporting for all buildings other than residential by 1 January 2022 (with residential reporting set for 2023) with the intention of commencing performance targets by 2027, trending to zero over subsequent years.

We need to follow this example and commence measuring the performance of our buildings. We need to set realistic target benchmarks for performance and begin the process of raising these benchmark targets over a number of years towards the ultimate goal of zero. An example of a draft timeline is provided below.

This means we need all new buildings to be providing LCAs for building designs at Development Approval (DA) stage and subsequently in applying for a building license. To begin, we could involve a number of Local Government Authorities in a pilot process in advance of the procedure being regulated within the NCC. This would initially involve requiring that all new projects submit LCAs as part of their DA packages. In the first instance, this would create an invaluable database across many projects of the current levels of whole of life carbon across all building uses. Collated data would assist in the next step of setting benchmark levels according to building types. Subsequently this could be extended for all major refurbishments.

Conducting a number of these pilots around the country would form a crucial database for moving to mandatory reporting and eventually setting requisite performance targets within the NCC. Once reporting is in place, a direction can be set for a pathway to zero through subsequent reviews of the NCC, sequentially elevating the performance levels towards zero.

Interestingly there is already one local government requiring LCAs to be submitted with DAs. The City of Vincent has been running this process for a number of years and now requires the achievement of certain benchmark thresholds of CO2/m2 according to building typology.

New Australian Standard

Underpinning the proposed new NCC requirements will be the need for a new Australian Standard guiding consistency in measurement and reporting. Much of current LCA practice stands on the European Standard EN15978 and others. The UK Part Z also refers to this standard. It will be important to get a new Australian Standard written in advance of NCC changes and a logical and simple strategy would be a modification of EN15978.

A potential timeline pathway could look something like:

- 2022 Piloting LCA reporting in a number of leading Local Government Authorities across Australia

- 2022 New Australian Standard for LCAs

- 2023/24 Lobbying the Australian Building Construction Board (ABCB) and state minister and state planning authorities to introduce mandatory reporting into the 2025 review of the NCC for all new building projects nationally

- 2025 NCC requires all new building license applications to submit LCA reporting

- 2027 NCC sets benchmark performance thresholds for whole of life carbon across all building types.

Performance thresholds could be elevated incrementally towards zero by:

- 2030 All new buildings have zero operational energy/carbon and a 50% reduction in embodied carbon

- 2035 All new buildings have zero whole of life carbon.

(Individual Local Governments Authorities could also of course offer development incentives for achieving zero earlier).

Of course there is nothing stopping individual architects initiating LCAs as part of their practice, getting ahead of the market. Arup have already announced that globally they will be doing LCAs for all their projects.

NOTES

Donaldson, Brogden, McLeod and Holland (2020) C-CAP: Coordinated Climate Action Plan: Report to National Council of The Australian Institute of Architects

Global Warming of 1.5°C Report, IPCC (2018), Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Canadell & Jackson (2020). Earth may temporarily pass dangerous 1.5°C warming limit by 2024, major new report says

Steffen (2018), Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene, Potsdam Institute

Ross Donaldson FRAIA, formerly group managing director and chairman of Woods Bagot from 2006 to 2016, now consults on strategy.