In the digital age there’s every reason to think that the photograph is taking over as the medium for how we read and understand architecture.

More accessible than the written word – and particularly architectural writing that’s heavily theoretical and excludes many from the conversation – an image captures and records a physical moment. But in the seeing of it, imagination can edit that moment, implying alterations and atmospheres that allow us to recognise something beyond the object of the image. So, it is both literal and highly subjective.

Few explorations of this idea are as compelling as John Berger’s 1972 opus, Ways of Seeing, a book that changed the modern world. In his introduction Berger wrote:

‘Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognises before it can speak… It is seeing that establishes our place in the world; we can explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.’

The same can be said of architecture. Whatever else has motivated or inspired it, architecture’s spatial purpose is – arguably – best understood by experiencing it ourselves, both as an object in space and as the space within an object. That’s not to invalidate the more considered explanations of a building’s conceptual origins, but it doesn’t make the scholarly review the only path to enlightenment either. Our lived experience may be less erudite and informed but is no less valid. As a writer/interpreter in this space, I’m equally drawn to the visceral response as I am to a scholarly metaphor.

To give culture – particularly the art world – a shakedown, Berger drew together threads of Marxism and art theory to supplant scholarly writing with the primacy of the image. He did it in a visual way, coupling post-Renaissance paintings of nudes with contemporary posters and magazine centrefolds, to prove how similarly they objectified women for the gratification of men.

Audience is crucial to any communication, because we perceive the world subjectively through the lens of our own experience and imagination. This makes the internet such a great enabler in the consumption of architecture – as well as everything else – with archi-porn from around the globe emailed, blogged, Instagrammed and tweeted 24/7. Thousands of projects with crisp headlines and saturated images. Filtering for meaning is overwhelming, so most of us toggle somewhere between surrender and retreat.

Berger reflects on cinematic editing as a crucial driver of narrative, using ‘long vistas and close-ups one after the other’ to craft a story that is not explained but implied. Much of architecture in the media uses this same tactic – to tease narratives out of photographs – but are all narratives equal?

No. In making the medium mainstream, the internet has democratised authorship. Notwithstanding the power of global titans to wield their influence by working the algorithms that harvest and distribute information online, today – in terms of tools and training – all you need to be a publisher is a smart phone and some digital images. No cadetship in journalistic ethics, balance, fact checking and proofreading, just photographs and a few lines of text. Digital publishers have capped our attention spans at 800 words and rarely like to test this limit. And let’s not even start on train-wreck TV shows like The Block or House Rules – a race to the bottom of the renovation-to-riches barrel – offering neither insight nor useful critique, just banal blabbering about taste and real estate value.

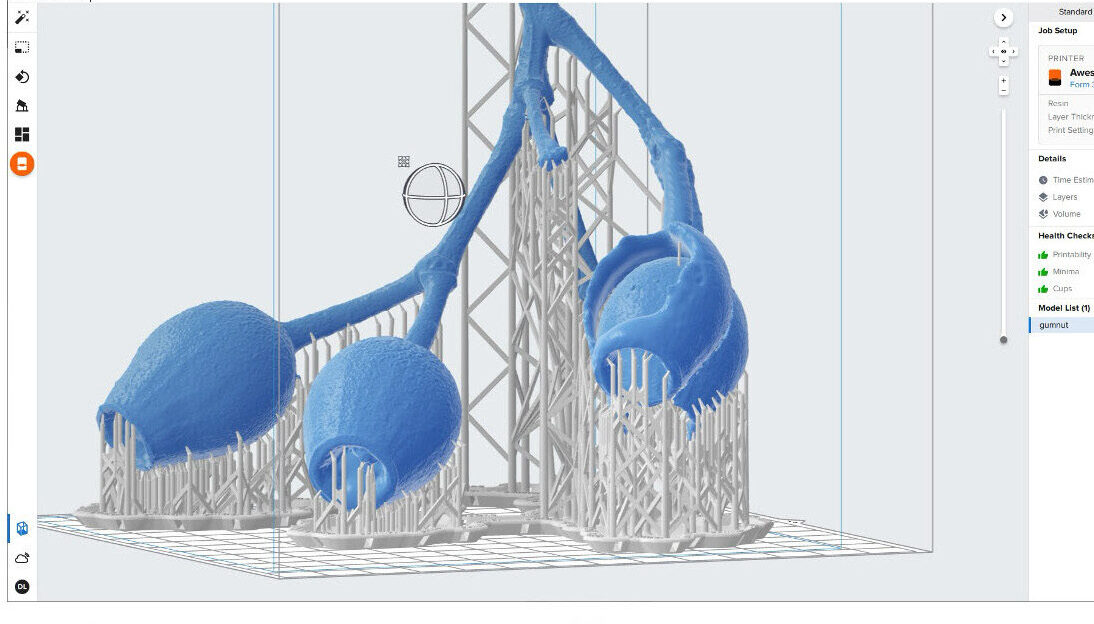

At the other extreme is the architects’ own austere website and self-published monograph. Both favour the image over the written word – by reducing barely legible typefaces to mere graphic imprints on a page – knowing that however much or little is written about a project, the images are incontrovertible and seemingly un-editorialised. Architects have long understood this; it’s the basis of their symbiotic relationship with photographers. Indeed, a number of eminent Australian photographers in the field have also studied architecture, creating an interesting chicken-and-egg scenario.

But understanding architecture for me is also experiential. I am not religious, but when I visited Jørn Utzon’s Bagsværd Church on the outskirts of Copenhagen, I was moved beyond words. I’d read almost nothing about this unassuming building, which from the street looks a bit like a warehouse. Perhaps my reaction was to the Utzon story. Perhaps it was because his church – all light, warmth and wit – was the incandescent opposite of the cold oppressive Catholic churches of my childhood, in which I felt diminutive and diminished.

Having spent a large chunk of my life mediating architecture and the thinking behind it to many different audiences – mainly through words but also through the curation of images – I’ve come to believe that words and images are equally important. Before Berger, the Gestalt psychologists of the early 20th century posited that in human perception the ‘whole is greater than the sum of its parts’. So, between words and images, combined in a thoughtful way, there may be no dichotomy at all. The image sets imaginations soaring, while the words ground it in context, so that each benefit from the other.

Peter Salhani is a freelance architectural journalist published online and in print, and a content creator for design-based clients. He is a former editor of architectureau and Monument magazine, and co-founder of sparkkle.space, an independent platform interviewing creatives from architecture, design and social action. From 2013-2020 he served on the NSW Architects Registration Board, representing consumers and the public interest.