Apartment design guidelines as architecture

In 2016, the Victorian government implemented the Better Apartment Design Standards (BADS) into the Victoria Planning Provisions (VPP) and all its planning schemes.1

These were positioned as a corrective reaction to the proliferation of low-quality apartment stock that had been built in previous years – joining a host of other frameworks, regulations, and stratagems that collectively parametricise the formal constraints and potentials of our built environment. Although initially criticised by the Australian Institute of Architects for not specifying a minimum dwelling size and for not mandating the use of architects, our Victorian Chapter generally supported the initiative as a way to improve design outcomes.2

This piece is not a lament for the diminished role of the architect. Rather, we want to speculate on the opportunities for architecture that might appear through an examination of the relationship between the architect and these modulating frameworks.

By 2021, the BADS had been revised and rebranded as the Apartment Design Guidelines for Victoria (ADGV).

Like BADS, the ADGV have statewide applicability: they are made actionable and enforceable through references within both the VPP and all its underlying planning schemes – specifically, through new clauses 55.07 and 58. While retaining a similar focus on quality design outcomes, these new guidelines became even more explicitly architectural in their remit. They included new guidance for external walls and materials, along with updates to the standards for open space (both communal and private), landscaping, and integration with the street.

It is here that we find ourselves wondering: with all these new mandated standards, what is left for us to design? And, if the design guideline has become a high-resolution placeholder for architecture, what new design opportunities might exist for architects?

Of course, regulation as form is not new to architects: in the 1920s, for example, Hugh Ferriss rendered Manhattan’s setback envelopes as a series of moody, art-deco volumes.3 The condition that we deal with today, however, is vastly more complex and constrained. If we were to repeat Ferris’ analysis on the contemporary Melbourne apartment, we would need to illustrate a tangle of so many interlocking formal relationships and constraints that an x-ray of a near-complete building would emerge – a nearly-architecture.

How are we to conceptualise the nearly architecture mandated by our current suite of apartment design standards and guidelines? The urbanist Keller Easterling uses the word disposition to make a distinction between the object forms and active forms of our built environment.4 For Easterling, the object form is the tangible content of architectural production: the building. The active form, meanwhile, is composed of all the immaterial forces, existing conditions, and interests that together shape the potential for the building to exist: this site- and object-specific potential is the building’s disposition. (Here, she draws a parallel with media theorist, Marshall McLuhan, who “highlighted the difference between the declared content of media – music on the radio or videos on the internet – and the means by which the content was delivered.”) Indeed, with the increased architectural specificity of the ADGV – coupled with the increasing financialisaton of housing – the active and object forms of new Victorian apartment buildings are becoming indistinguishable; the building has become closely coupled with the form of its disposition.

Consider any prospective site for mid- to high-rise residential development. Typically, the developer will have an idea of the net saleable area (NSA) required in order to make the venture profitable, even before an architect is engaged. The NSA can be thought of as a formula that is applied to the geometry of the site, resulting in a cellular three-dimensional volume that has been sculpted by planning limitations, such as setbacks and height limits. At this stage, the disposition of the project is explicitly formal, but this form does not have an author. Rather, it is an automated, volumetric consequence of the interaction of active forms. The role of the architect, then, is to leverage the potential of this active form to author some final object form: in other words, we must convert disposition into architecture. There are, in theory, many possible object forms that may arise from a single, situated active form. In practice, however, the increased architectural specificity of these regulatory active forms has led to fewer and fewer possible object forms.

Where once the volumetric form of a feasibility study would barely resemble a building, the new design standards for apartments (ADGV) mandated in Clause 58 now provide an architectural structure. The National Construction Code (NCC) and Australian Standards – other active forms contributing to a building’s disposition – cannot script buildings through translation alone, but through the structure of clause 58, their logics can be embedded prior to design. An undesigned building template can now be generated in relative autonomy.

Some lines of causality in the apartment provisions are obvious: room depth and ceiling height are bound by ratio; the dimensions of the kitchen are bound to the living room; bedrooms must connect to the building envelope for daylight access. But some lines of causality are less obvious. A window, for example, has obvious contingencies with the envelope of the building, and is thus indirectly related to property size, scale, and orientation – along with the building as an economic composition (NSA). Where natural ventilation is required (40% of apartments per floor), the minimum and maximum distances between openings provide an additional layer of spatial configuration to the apartment over the programmatic layout. This plays a role in the location, quality, and – arguably – the cultural and market understanding of the bathroom, which is now a by-product of other provisions. The discrete habitable container of the apartment – now a relatively finite constellation of parts – is then strictly patterned across and bound to floor plates in response to noise attenuation and apartment diversity standards. A minor adjustment to a single apartment design now has traceable architectural consequences throughout the entire building.

Through this complex, parametric part-to-whole relationship, the design of the object form of a building is preempted by the autonomous interactions of all the active forms at play – which over-constrain the building’s disposition, narrowing the scope of possible object forms. The legislative is now explicitly architectural.

This is not to say that our current (proliferating, tightly constrained) standards are not capable of producing good architecture: our experience is that good architects will always find a way to make good buildings, regardless of the constraints. But the increasing specificity of apartment design standards does result in a tightening of constraints, giving good architects fewer and fewer possibilities for innovative or novel design. Similarly, for the minimally compliant projects that make up the bulk of our state’s housing stock, buildings become generic, physical manifestations of their regulatory dispositions.

This repetition of a generic apartment model reinforces assumptions about the ideal dwelling. Today, the open-living typology is practically uncontested – bedroom and living room dimensions assert their sub-architectural componentry, which in turn reinforces entrenched sociocultural expectations; the TV is protected by the standards, while the piano and the home office go unrecognised. Suddenly, everything is rounded to its average; nothing is exemplary.

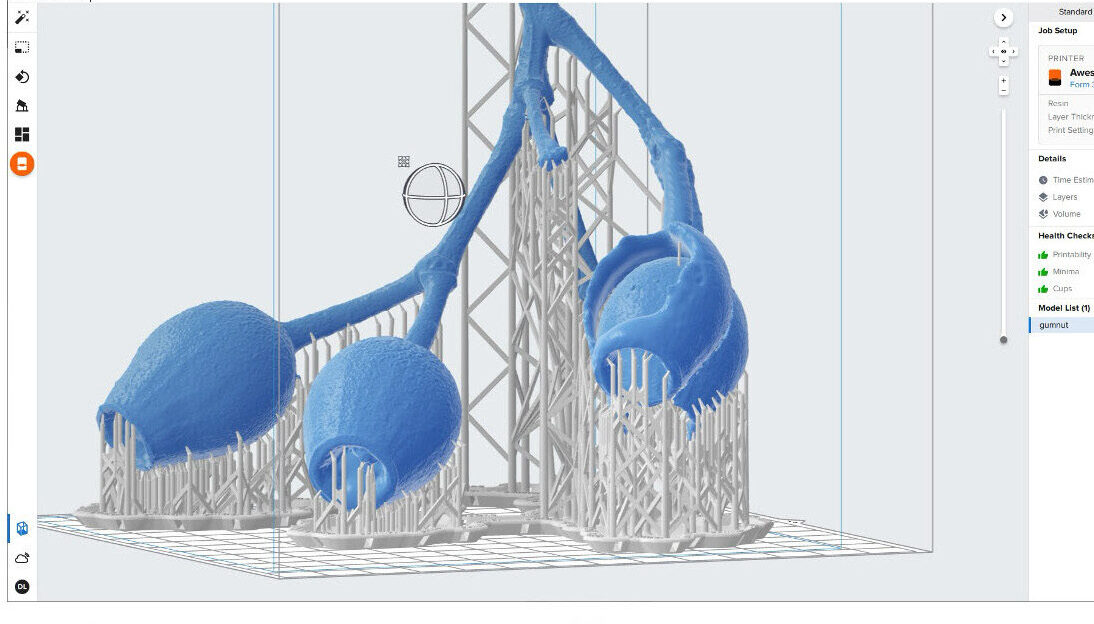

For the discipline and profession of architecture, the increasing architecturalisation of design standards has far-reaching consequences – including a growing perception among property developers and so-called PropTech (property technology) companies that architectural production can now be wholly automated. In Victoria and elsewhere, software is already being used to accelerate land speculation and feasibility processes. Through these new platforms, possible development parcels can be instantly identified by inputting orientation, size, proportion, zoning, overlays, proximity to public transport, and other spatially calculable considerations; design optioneering can be automated by manipulating desired NSA, building height, and other parameters – even architectural style. In theory, the automation of certain broad-strokes massing and feasibility analyses could free-up time (and budget) for architects to re-allocate elsewhere in a project. In practice, though, the co-opting of these tools by property developers only serve to maximise profits for developers while further minimising the architectural scope of work.

Rather than fretting about the automation of our profession, we see an opportunity here for the role of the architect to expand; to encompass designing the active form of a building, rather than just its object form. It is easy to imagine that the computational logics underpinning existing BIM and parametric software could be adapted and redeployed to also test variations of our design standards and guidelines (active forms), in addition to our buildings (object forms). Here, we suggest that the ADGV might be a useful pilot, given that it already closely calibrates a building with its disposition.

Perhaps software could allow us – architects, designers, planners, and spatial practitioners – to see (and manipulate) the spatial and formal consequences of different variations to design standards, guidelines, and codes. Perhaps standards need to be reimagined as dynamic and adaptive design tools, rather than static instruments.

What might this achieve?

- Perhaps we would begin to see better interoperability and balance between spatial legislation, architecture, and property development. We suggest that the feasibility process might become a more equitable venture between these disciplines.

- Perhaps we would be better placed to test the efficacy of design standards in real time, and then update our rules in response to feedback. We suggest a rapid-prototyping approach to planning, so that issues can be quickly corrected.

- Perhaps we would be able to pilot novel and innovative housing models in isolated circumstances, without compromising the integrity of the wider planning system. We suggest that computational approaches could be leveraged to identify opportunities for calculated risk – the results of which could feed back into the wider system.

- Perhaps we would even be able to implement multiple versions in parallel. We suggest that the simultaneous governance of a series of different (but complementary) generic models could allow for controlled heterogeneity in our cities.

- And perhaps these shifting, adaptive standards would help the broader public build greater critical literacy about both planning and architecture – culminating in a more productive and expansive discourse. We suggest that the ongoing implementation of dynamic planning controls would encourage broader public debate about the formal and spatial consequences of planning-as-architecture, as citizens could see new buildings spring up in response to new standards or clauses.

Apartments in Victoria are only one example of growing rifts and tensions between the competing interests of capital, regulation, and design in the built environment. By contemplating the relationships and power structures between object forms and active forms, we suggest that architects may conceive of new ways to affect the city – but this demands a close, critical engagement with our present condition. As design standards and guidelines become increasingly architectural to safeguard quality design outcomes in minimally compliant projects, those of us with architectural expertise must become more involved in policy-making processes. Perhaps, rather than lamenting our diminishing roles, it is time – as Easterling suggests – to expand the role of the architect, to encompass design of the active forms of our buildings, in addition to their object forms in a manner where the interplay between them becomes a subject of our design.5

Notes

Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning. 2016. Better ApartmentsDesign Standards, State of Victoria.

Australian Institute of Architects. 2017. “AIA Comments on New Design Standards for Vic Apartments,” ARCHITECTURE & DESIGN (blog), May 9, 2017, https://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/news/new-design-standards-aim-toimprove-liveability-in.

Ferriss, Hugh., 1929. The Metropolis of Tomorrow. New York NY: Ives Washburn.

Easterling, Keller., 2014. Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space New York, NY: Verso: 13-14.

Easterling, Keller., 2021. Medium Design: Knowing How to Work on the World Verso Books: 38.

Allan Burrows RAIA Grad. is an architectural graduate at John Wardle Architects. He has led design studios at the University of Melbourne and RMIT University, researching architecture as a consequence of, and an agent within, interdisciplinary systems and institutions.

Arjuna Benson RAIA Grad. is a graduate of architecture, currently working at Sibling Architecture. He is a tutor at RMIT and has also taught at the University of Melbourne. Through his work, he is interested in the junctions between architectural speculation and reality.