Unbuilt and speculative architecture

Withdrawing

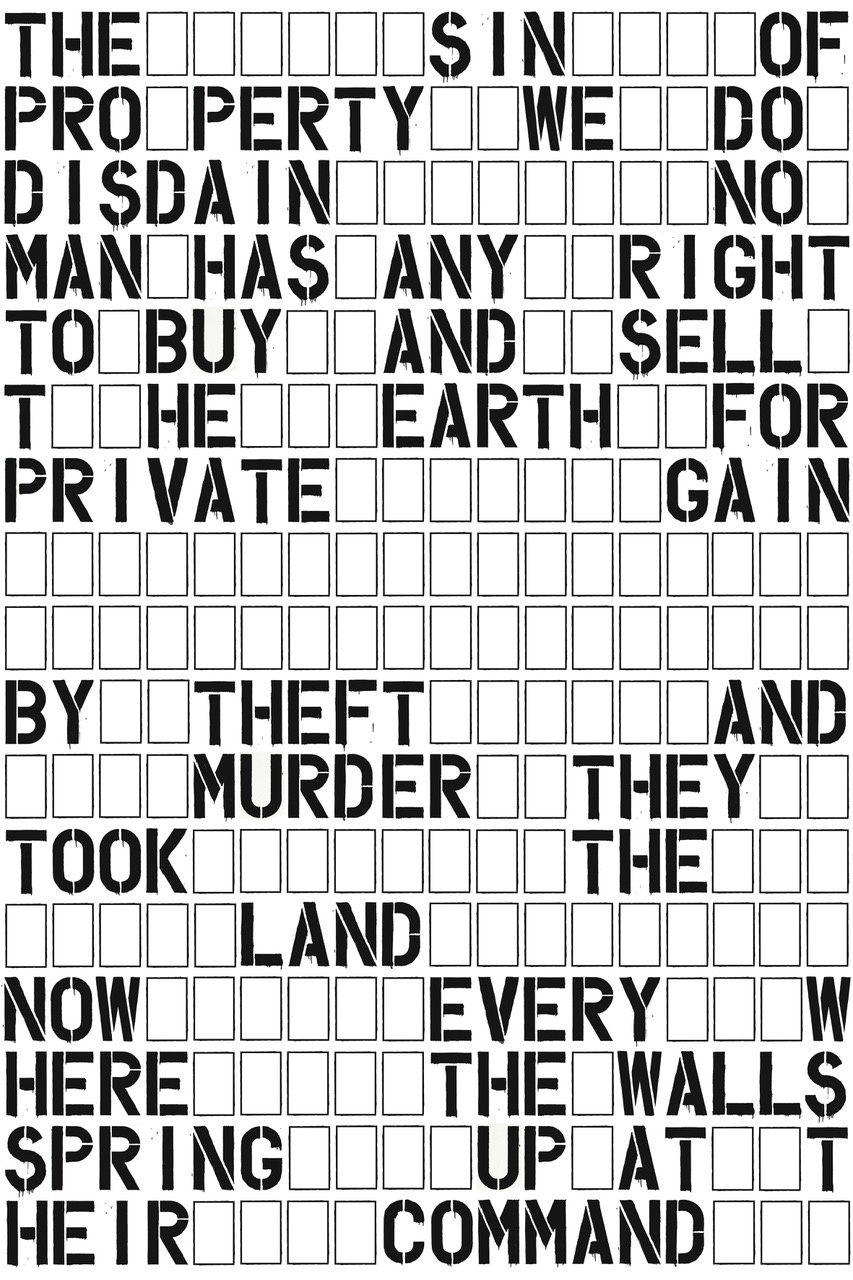

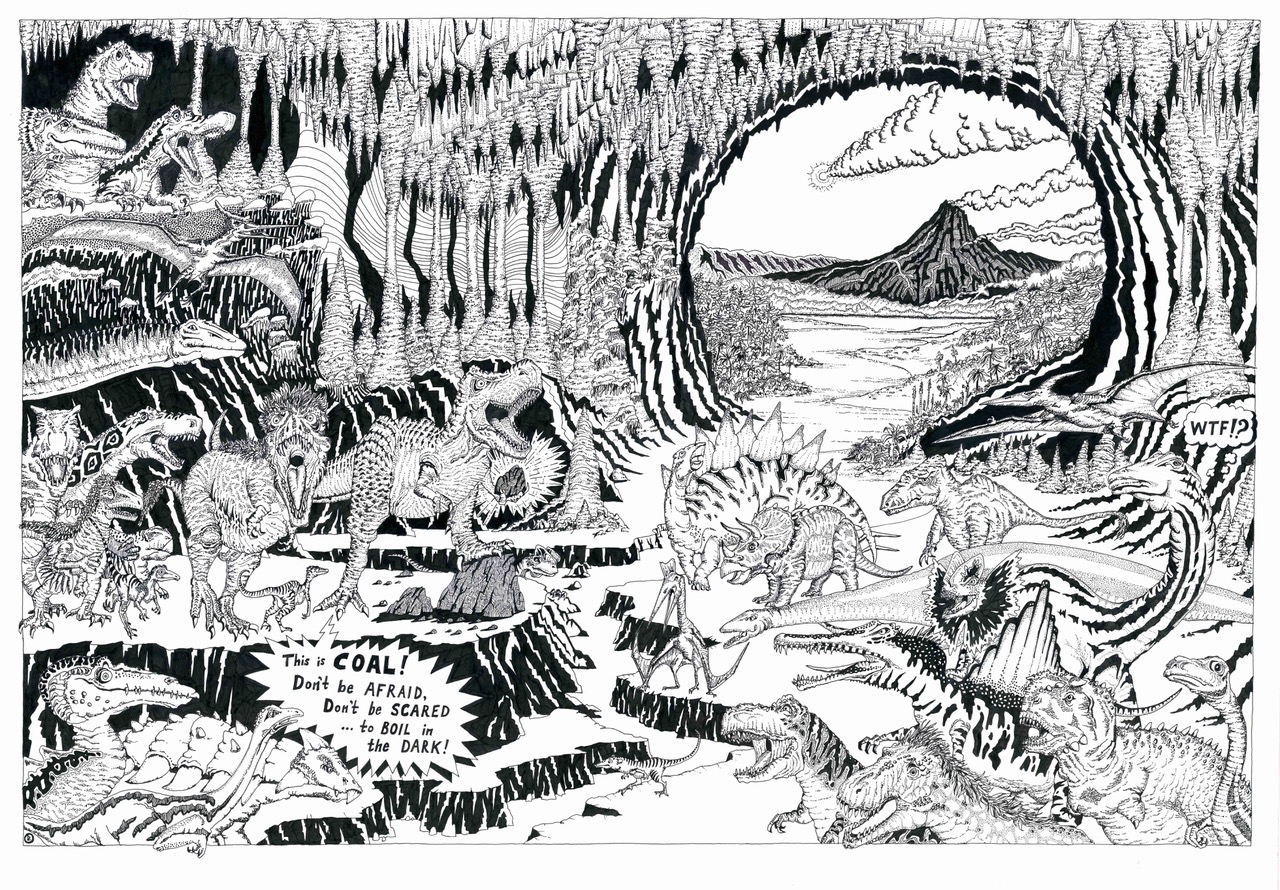

Architectural practice, for better or worse, is at the mercy of the ebbs and flows of larger societal forces, whether that be the political, economic, or, as we find ourselves in now, a global health crisis. So too, architectural drawing, as a medium, and the architectural exhibition, as a site, have often occupied an indexical relationship to architectural practice, flourishing in the periods of disruption and dormancy. It was in the chaos of the French Revolution and its aftermath, that the utopian drawing practices of Etienne Louis Boullée, Claude Nicolas Ledoux and Jean Jacques Lequeu emerged as a counter narrative, when the architectural drawing became a framework for the exploration of fantastical architecture, compensating for the practical inability to build. While in the 1950s, Emil Kaufman termed these practices ‘revolutionary’, it was less in the sense of political revolution and more in the sense of an escapism through the discipline of drawing. Indeed, for Lequeu, who served as a government draughtsman for some of this time, it was an escape from the political pressures of post-revolutionary power structures. On the back of his drawing The Gate of Parisis (1794), he scrawled: ‘a drawing to save me from the guillotine’.

Similarly, the immediate aftermath of World War I coincided with a period of enormous architectural ambition, and incredibly limited opportunities to build. This saw the flourishing of a range of avant-garde practices and movements, including the Futurists, the Expressionists, and de Stijl who all used drawing as a framework to critique the present and propose models of the future. Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin (1925), Mies van der Rohe’s Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper Project in Berlin Mitte (1921), or Eileen Gray’s painted or drawn rug studies (c.1910-1930), are as iconic as any of the built works of modernism, as a result of the polemical impact of the imagery and its ability to be disseminated through an emerging publication industry to a diverse and sometimes disconnected audience. When combined with the inability to realise architecture for a generation of highly talented individuals, drawing offered an alternative mode of engagement, but also a freedom from the economic and political realities that underpin so much architectural production in the real world.

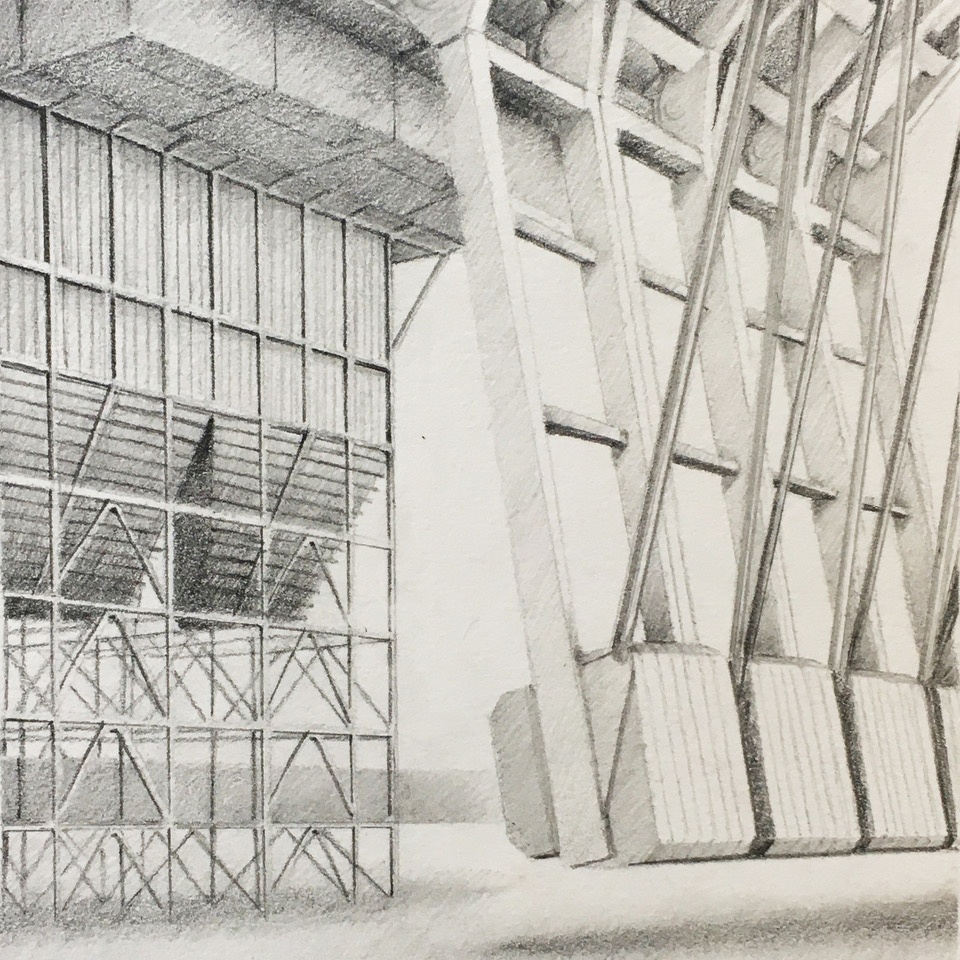

While the aftermath of World War II saw an explosion of opportunities to build, and an architectural profession grappling with the scale and scope of this reconstruction project, by the 1970s, things had slowed considerably and drawing again emerged as a mode of expression or engagement. In this period, architectural drawing emerged as a medium in itself, and was no longer seen as merely a representation of future built architecture, but a standalone mode of expression and, in some cases, commodification. As Kaufmann argues, in its most extreme form, buildings were reframed as the mere representation of architectural drawings, rather than the other way around (Kauffman, 1970-90).

This period saw the architectural exhibition also emerge as a space of critique, escape and even disenfranchisement, in the work of Archigram in the UK, Hans Hollein, Walter Pichler and Raimund Abraham in Vienna, and a host of emerging drawing practices in New York (John Hejduk, Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves and many more) that supported a vibrant but exclusive gallery scene where architectural drawings were both shown and sold as commodities in their own right. The artistic drawing practices of Rosalind Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, and conceptual artists such as Sol Le Witt or Hanne Darboven, also played a role in the same period in repositioning drawing not as an adjunct or precursor to creative practice, but as the practice itself. (Stout, 2014: 14). The foundation of The Drawing Centre in New York in 1977, seemed to formally acknowledge this emergence of drawing as an autonomous medium of cultural production in its own right. It was on the back of this expansion of architectural drawing, and its increased cultural presence through the exhibition globally, that the iconic architectural drawing practices of the 1980s, from Shin Takamatsu in Japan, to Lebbeus Woods, Daniel Libeskind and Neil Denari in the US, and Zaha Hadid, Marion Vriesendorp and Coop Himmelblau in Europe emerged and, in many cases, became a springboard for future success and recognition in the profession. Simultaneously, new discourses around architectural drawing and exhibition began to emerge (Betsky, 1990 and Kipnis, 2001). As a cultural paradigm, drawing offered a mode of engagement outside of the conventional forms of architecture and beyond its social, economic and political obligations. At the same time, it offered a platform for recognition and exposure within that same professional context through its reproducibility in publication and accessibility in the gallery.

Perhaps what we learn from these extraordinary drawings is the extraordinary context they were born from. There is little doubt that we find ourselves today at a similarly extraordinary moment in time. Drawing, whether as an act of catharsis, as documentation, as provocation, or as emancipation, provides a means of understanding the world, and architecture, and our relationship to it. It is at moments such as this, that perhaps what architects do best is draw, and the drawing is still the most effective litmus test that our profession has available to it.

In this sense, the architectural drawing is more than just a proposition. It is the ultimate act of optimism. It creates a site for critique, discourse, politics and escape. But it also creates a space of connectivity and exchange, exploration and collaboration. With the shift to working arrangements, the restructuring of practice and the general uncertainty around the future, the role of architectural drawing, as both an adjunct to practice but a mode of critique is once again pertinent. As human interaction has been distanced through COVID-19, drawing provides an immediacy to ideas, thoughts, debates and critique that supplements the conversations that are happening at a broader cultural level. As we rethink the nature of our profession, and the relationship this profession has to the broader planet, drawing provides a mode of dialogue that can reshape these questions.

By withdrawing from physical contact, at least in the short term, drawing enables us to both step back and to step into new narratives that are forming around us. To withdraw is to escape an overwhelming situation and return to safe ground, occupying a more defendable position. In a way, for architecture, that space is drawing. It allows us to reassess before entering back into the fray. One thing that is especially clear, is that in times of chaos, panic or uncertainty, there is as much power in picking up a pencil, as there is in driving a bulldozer. Withdrawal is a powerful act.

Notes

Betsky, Aaron. Violated Perfection: Architecture and the Fragmentation of the Modern (New York: Rizzolli, 1990)

Kauffman, Jordan. Drawing on Architecture: The Object of Lines, 1970-1990 (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 2018)

Kipnis, Jeffrey. Perfect Acts of Architecture (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001)

Stout, Katharine. Contemporary Drawing: From the 1960s to Now (London: Tate Publishing, 2014)

Michael Chapman is Professor at the School of Architecture and the Built Environment at the University of Newcastle. His research explores architectural drawing and its theory and scholarship, specifically in relationship to politics, industrialisation and modernism.

Dr Timothy Burke is a lecturer of Architecture in the School of Architecture and the Built Environment at the University of Newcastle. He has been researching and teaching at Newcastle since 2015 and currently leads the final year Master of Architecture studio.

This article was written in response to the NSW Chapter Editorial Committee’s call for contributions in a context of crisis, seeking perspectives on What are we doing?