Two-way learning is the foundation of participatory design and construction. In our experience it is central to First Nations cultures with many having a specific word or phrase for this way of doing. Two-way learning sits at the core of our practice and was the genesis of the way in which we practice.

Kaunitz Yeung Architecture was born from the approach that David began developing while living and working in the remote Solomon Islands. With little English spoken or connectivity to the outside world, projects were delivered through true collaboration. This approach has continued to develop as our experience and the number of communities we have collaborated with has grown. This has been amplified by those within the practice such as Ka Wai Yeung, Emma Trask-Ward and Marni Reti as they have folded their own perspectives and experience into our process.

Kaunitz Yeung Architecture’s deep commitment to participatory design and local construction is central to the story of belonging for each project. The former builds a rapport and ownership between the project and the users. The later enables an enduring connection to place and Country. This also serves as the primary measure of the project. These are the outcomes that really matter if architecture is to be an agent of social change and elevate its standing within the community at large.

Underlying this is the fact that all our work has been delivered within the same funding and time constraints as other similar projects. We consider this important as it reinforces the legitimacy of the approach by being respectful of the community’s limited resources and opportunities. It has also demonstrated that high quality, change making architecture does not need to be a luxury item.

Many of the communities we collaborate with face the very real challenges of living in two worlds. For us architecture is a vehicle to unite these two worlds. Through our experience we have developed an approach, a process which harnesses the projects cultural context. By working together with communities and being brave we are able to create architecture which is elevated beyond what normally could be achieved. The result, we hope, is the best of both worlds.

The foundation of this process is mutual respect. You must acknowledge what you do not know and open yourself up to two-way learning.

This requires a humility in approach. The design process must be opened to the clients and users. In this way the clients / end users bring their knowledge of their cultural world to the design process. They bring what the design team lacks. This compliments what the design team brings to the project experience, best practice, and expertise. In this way the best of both worlds can be achieved.

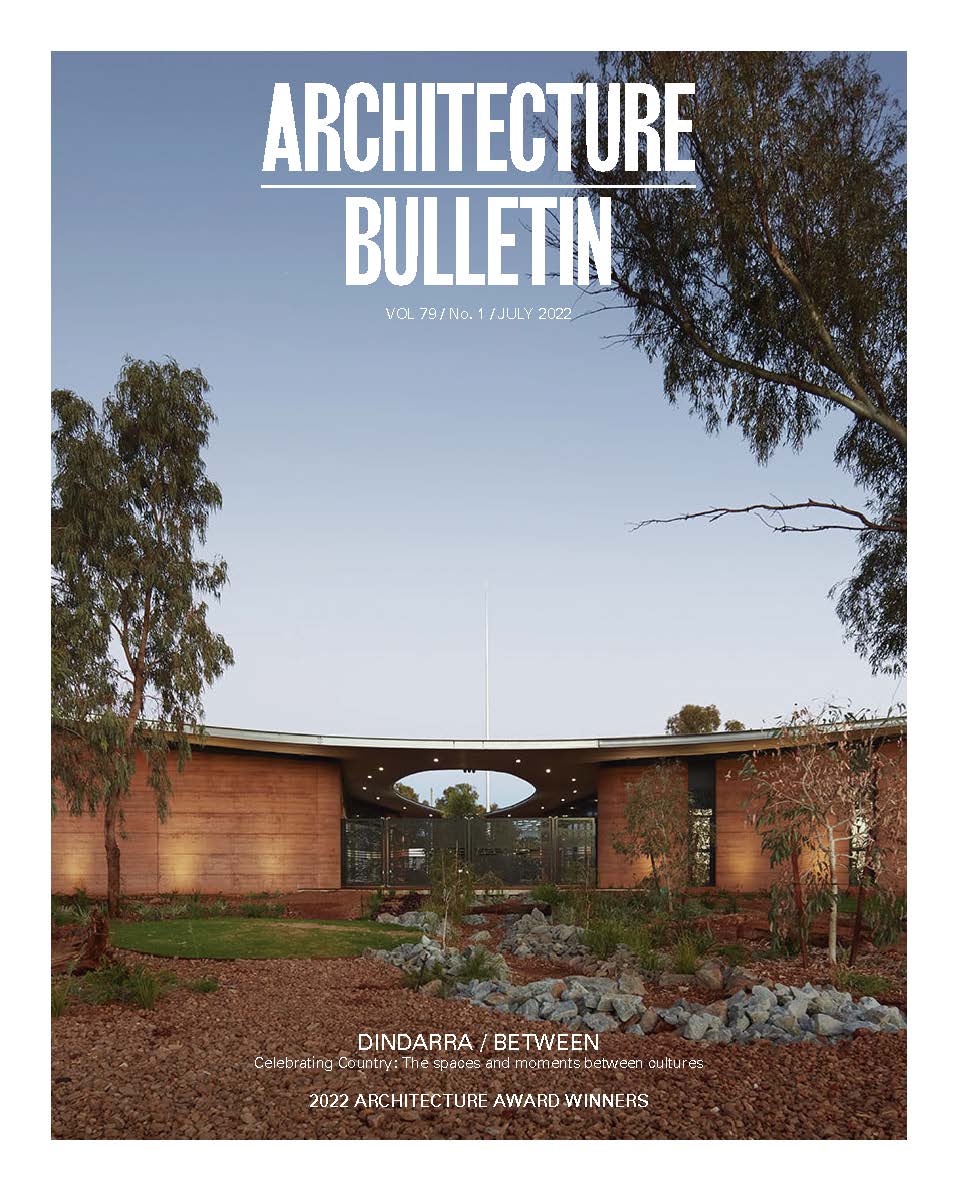

Our experience over the last ten years working with almost all the Ngaanyatjarra, Martu Niaboli communities in the Western Australia deserts has also been central to our approach. The culmination of the desert project collaborations is the recently completed Puntukurnu Aboriginal Medical Service (PAMS) Clinic in Newman WA on Nyiyaparli Country and servicing all four remote Martu communities.

The project has closely followed the following eight principles which we use to guide all our work. The response to each principle has been applied in a way that is specific to local people, culture and Country.

1. Community-led consultation: The key to this is to work with the existing community governance structures. The PAMS board is made up of a female and male member from each of the four Martu communities and Newman. We worked through these representatives for several years supporting them to engage with community and facilitate our direct engagement. Importantly this enables consultation to occur in language which supports principle two.

2. Enabling all voices to be heard: Multiplicity of forums is important in enabling all voices to be heard. Small group meetings with women, men, youth, children, Indigenous health workers etc. are important to enable specific perspectives to be conveyed. So too is informal discussion at the shop or sitting under a tree.

3. Time to listen: Perhaps the most important aspect of engagement and consultation is time. It takes time to build rapport and relationships. Only with time can there be repetition in engagement that enables a real understanding to be developed and issues to be uncovered. We spend significant time in communities and on Country and this was especially true of our years working with the Martu communities culminating in the PAMS Clinic Newman.

4. First principles approach: Every project goes through a rigorous process where nothing is assumed, and everything is revalidated. The PAMS Clinic was no different with all aspects of the project being redefined from our previous work and lessons learnt appropriately applied.

5. Iterative co-design: The first four principles cannot be successful without an iterative process that is an authentic partnership with communities, the client and stakeholders. In Newman this was seamless with our previous work with PAMS and the Martu communities. The process was a journey for all concerned where the logic of decision making was crystal clear to all involved.

6. Materials / art / culture: Local materials and integration of local art are hallmarks of how we connect architecture to Country. Rammed earth creates a human and intuitive connection to its place.

The material is Country. It reflects the different light and absorbs the rain just like Country. This is obvious and immediate to everyone but elevated and important for Aboriginal people. The excitement in the community for the project was palpable once the rammed earth walls were erected well before the project was complete.

7. Co-construct: This is in many respects the hardest principle to achieve in Australia. In the Pacific almost all the projects we have worked on have been completely built by local people. We are expanding our collaboration with Indigenous contractors and communities to raise the bar and steadily making progress.

8. Innovation: No matter the budget or the remoteness we feel innovation must be central to any project to deliver the best possible outcome for communities. In Newman the rooftop PVs mean that the building is almost entirely powered from onsite renewables. Dramatically reducing operational carbon and running costs.

In particular the integration of art has been emblematic of the implementation of these eight values. It is important in enriching the architecture, engaging with, and providing an enduring connection to local people. The process of selecting art is always conducted by the community and guided to ensure the artists represent the gender and other diversities of community. This is not simply a copying exercise but a process of iterative collaboration with the artists to ensure the integrity of the art and its cultural meaning are maintained while it is adapted for integration with the architecture. Art counters the utilitarian-built environment of most underprivileged communities which gives no inkling of the extraordinary art that is so often created for the pleasure of others. Their incorporation enables the building to pay respect to elders, artists and culture, enriching the community, becoming a beacon of a brighter future.

It is this brighter future that we hope participatory design and construction by two-way learning will engender. A future in which the best of both worlds is achieved.

Marni Reti is a proud Palawa and Ngātiwai woman, born and raised on Gadigal Country. She graduated from a Master of Architecture at UTS, where she was one of the first recipients of the inaugural Droga Indigenous Architecture Scholarship, and the 2021 recipient of the NSW Architect Medallion. Marni is a graduate of architecture at award-winning practice, Kaunitz Yeung Architecture. She has dedicated her professional and academic career to engaging Indigenous Knowledge Keeping into architectural practice and design.

David Kaunitz as a director of Kaunitz Yeung Architecture is focused on facilitating high-quality architecture in some of the most disadvantaged communities in Australian and Asia–Pacific. Underlying this is a deep commitment to participatory design and local construction. They have a significant body of award-winning architecture and have worked in more than 40 Aboriginal & Torres Strait Island communities, 200 Pacific Island communities as well as in Asia. This includes prestigious awards such as the Union of International Architects, Vassilis Sgoutas Prize the world’s highest architectural