In an interview a few years ago, I was asked how my upbringing has shaped the way I practice architecture. Why equity in practice was so important to me and what drives me to question craft and function. A few years later, that same question was asked with a follow-on question – how has that upbringing on Country shaped me as an architect? The answer to this is through this yarn.

I arrived in Australia in the early 80s though the Refugee Resettlement Scheme. I had no recollection of Vietnam. My first memories were of Alice Springs where I lived in a co-living estate with six other refugee families. The place was basic and not particularly beautiful, but it was functional and provided a communal courtyard where I spent my days playing with the other refugee children. Life was simple, I felt safe, happy and I had a community to which I belonged.

For my parents, Alice Springs was a world away from what they knew. They felt a deep sense of loss for the country they were forced to flee but an immense sense of gratitude for an opportunity to build a better life. They were surrounded by a strong network of friends and supported by our very generous Australian sponsors who helped them find work, education and most importantly integration with the broader community of Alice Springs. For them, it was about being empowered to make choices and a need to give back to the country they now called home.

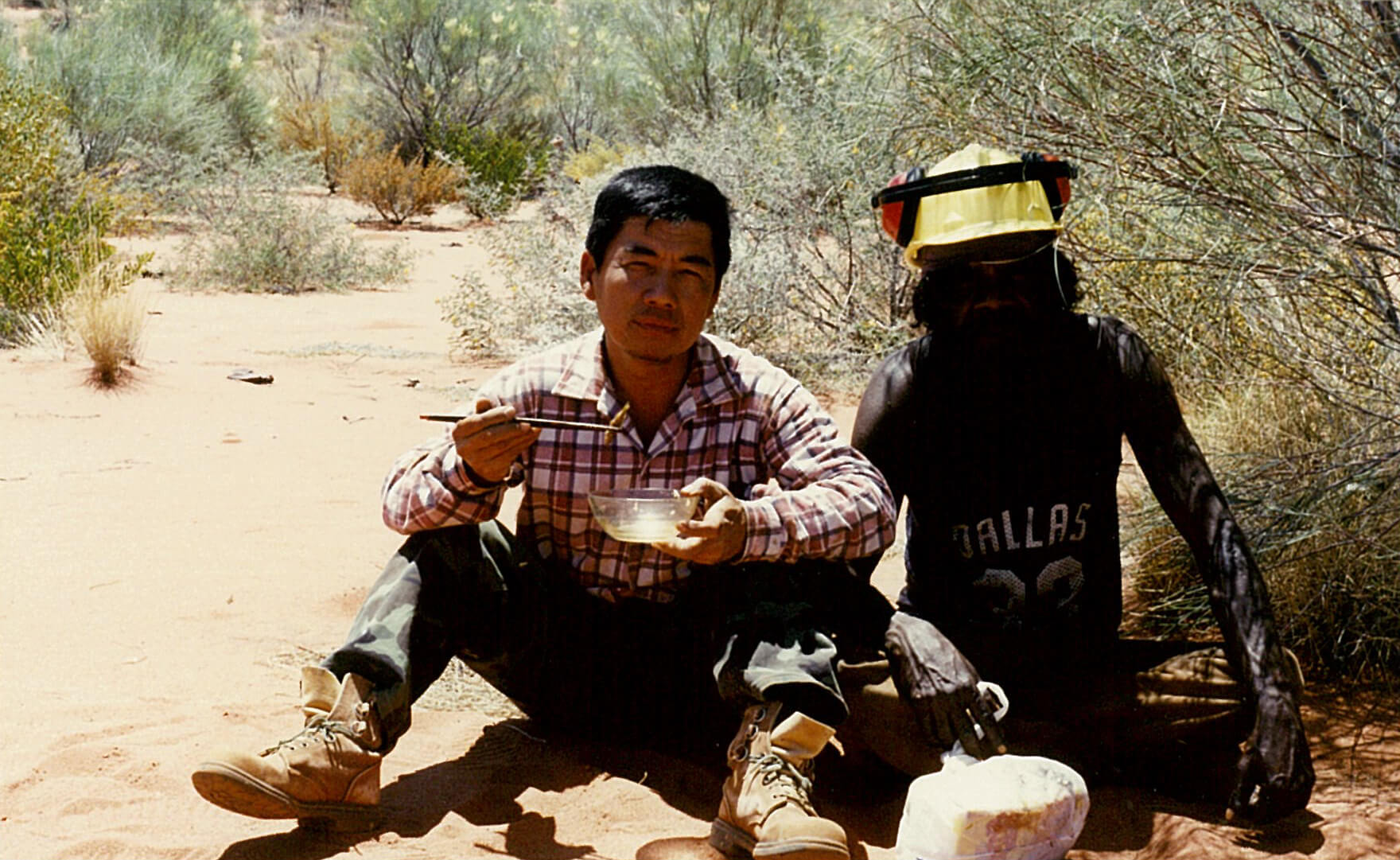

Within a few years and through the great support of many advocates, my father established his own construction company and was building basic facilities for Indigenous communities in the Kimberly region. Due to the remoteness of these projects, he would be away from home for many weeks at a time. During my school holidays, I would join him “out bush”. It was eye opening. The structures he built were very basic, they provided a space for shelter, shade and protection from the elements. However, they were incredibly uncomfortable to occupy and very crudely put together.

Despite this, I observed a great camaraderie through working with the Indigenous communities. Through a shared and mutual respect, my Dad and his team interacted with the community to find different ways to communicate and work together. As a child watching the process, it was comical at times, sometimes stressful but mostly productive. Although the final buildings were basic, they were proud of what they collectively achieved together.

This experience of growing up in Alice and my time “out bush” with my dad established why team work and collaboration underpin how I practice as an architect. Traditionally architecture is recorded as an outcome. It is critiqued on its beauty, its craft, its function – how it contributes to its place and the people who use it. All these things are extremely important, but very rarely do we hear about the process of how it was made and the community of people who contributed to it beyond the hero architect. This recognition and acknowledgement of the many hands and minds which contribute to the making of buildings is critically important. From equity in the workplace, giving everyone a voice; hearing people’s stories, understanding how difference can enrich a project; acknowledging contributions; advocating for people; finding balance – these all shape the culture of the profession and enhance what we can collectively produce.

Observing the built outcomes “out bush” also made me question the fundamentals of what we need as human beings and if those same needs can both be functional and beautifully crafted to celebrate how we occupy place. In recent years, Designing with Country has become a refreshing core requirement for many projects that reinforce understandings of place and people to inform processes of making architecture. It promotes a critical need to deeply understand these stories of place and people and for better representation of voices from less visible cultures. It also supports the idea of adding our own stories and how the collective experiences of all of us can enrich the way we craft and make buildings for their place and the people who occupy them.

These principles have been embedded in various ways through early engagement with First Nations collaborators on projects over the years. On a large metro-precinct project, embedding stories of place were explored through the selection of Indigenous artists for each building on the site. Rather than treat the art as an overlay, each artist’s interpretation was integrated into the design of the buildings, resulting in a rich tapestry of responses for the facades, built form and spatial design. On a competition for a large public performance space, consultation with our First Nations collaborator adopted a more ephemeral response. Centred around how fire was used on the site for ceremony and gathering, charred timber and specialist lighting was designed to celebrate the transient interactions of the people who would visit the place both past and present.

Circling back to those earlier questions, my early years in Alice Springs and those trips out bush with my dad have shaped how I practice through a collaborative approach and the ambition to produce architecture that is both functional and beautifully crafted for its place. It is an acknowledgment of our different stories and a recognition that diversity and a respectful collective culture can achieve great outcomes together. Furthermore, it provides fundamental qualities that bind us through a sense of belonging to a place and a desire to find a community.

Chi Melhem is as an architect with a breadth of experience across typologies and scales. Before recently establishing EMBECE, Chi worked with Tzannes for almost two decades. As a director at Tzannes she delivered significant projects from urban design, feasibility, multi-residential and bespoke houses to landmark cultural buildings. Chi is an advocate for equality within the profession, has co-led the Masters of Architecture housing studio at UNSW and is a member of the NSW State Design Review Panel.