An ambition of our practice since we started eight years ago has been to explore and find ways to embed cultural, environmental and social value in our work. We believe that valuable architecture must balance functionality with poetics, nurture community and connect people, not only with each other, but with the broader world around us.

To do this, we have sought to work in a way that emphasises our methods of practice as being equally important to the architecture that we produce. We do this by always considering the intangible aspects of a project as much as the tangible ones. This method values conversations and relationships, long term learning and experimentation, writing and documentation of ideas – much of which (to this date) has been in the delivery of small acts and works, that are now progressively growing and being realised.

One of our most important current collaborations is with cultural spatial designer Danièle Hromek (Budawang /Yuin) – with whom our work and conversations have been ongoing since we met over three years ago. The Redfern Community Facility, commissioned by the City of Sydney, has been an opportunity to develop and strengthen our ways of working together.

This community facility is situated on Gadi Country. Gadi land extends from Burrawara (South Head) through to Warrane (Sydney Cove), Gomora (Cockle Bay to Darling Harbour) and possibly to Blackwattle Creek, taking in the wetland sand and dunes now known as Redfern, Erskineville, Surry Hills and Paddington, down to the Cook’s River. The neighbouring clans are Cameragal (to the north), Wangal (to the west) and Gameygal (to the south).

Sited on a prominent corner in Redfern, the contemporary significance of this place for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members should not be understated. Redfern is, was, and continues to hold great community significance as a place of activism, social resistance and change.

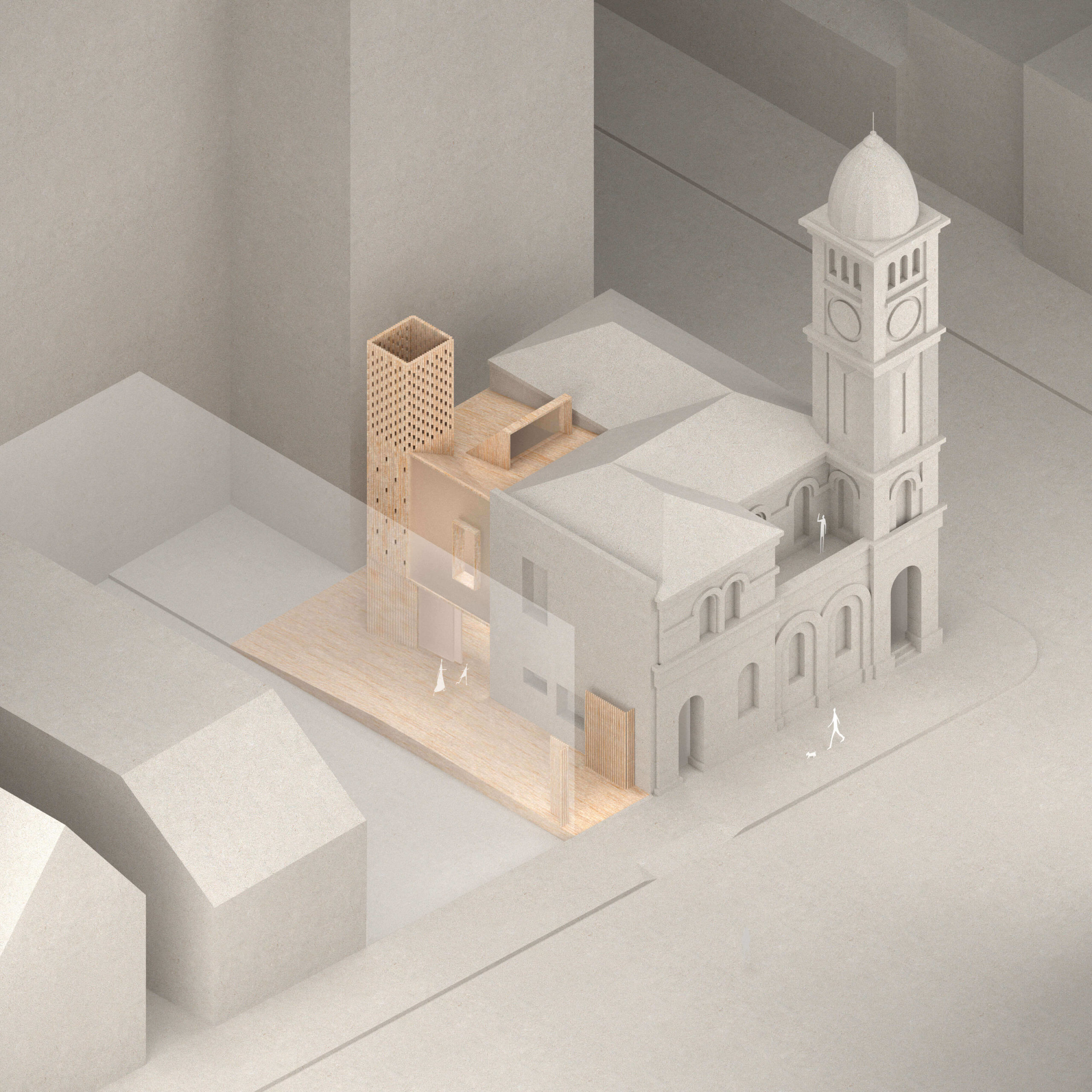

The project is for the upgrade of an existing 1880s Victorian Italianate building, the brief to make it both physically and psychologically accessible to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community for whom this facility will serve.

While it might seem to some that keeping the existing colonial building relatively intact is symbolically problematic in this context, there are a number of narratives that inform and result from this decision. Firstly the building was chosen by local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community representatives for the community. Secondly, the existing 1880s building was constructed from materials of this Country – local Sydney sandstone quarried from Pyrmont and bricks made from clay deposits most likely sourced from the brick pits around this area. These materials continue to hold stories and significance that should be recognised and valued.

Working collaboratively with Danièle, building heritage specialist Jean Rice and architectural historian Noni Boyd, our approach to this project seeks to celebrate and honour a cultural reading of place. Seeking to design specifically for a broader cultural, environmental and social context over an extended period of time.

A robust design and materials strategy that values what is existing on the site and the embedded memory of these materials is crucial. Our approach extends beyond the boundaries of the site. It is a framework for the current upgrade works as well as future works, with an ambition to provide a project that celebrates, considers and recognises existing scars, and will leave a positive legacy for the community and all who will visit this place.

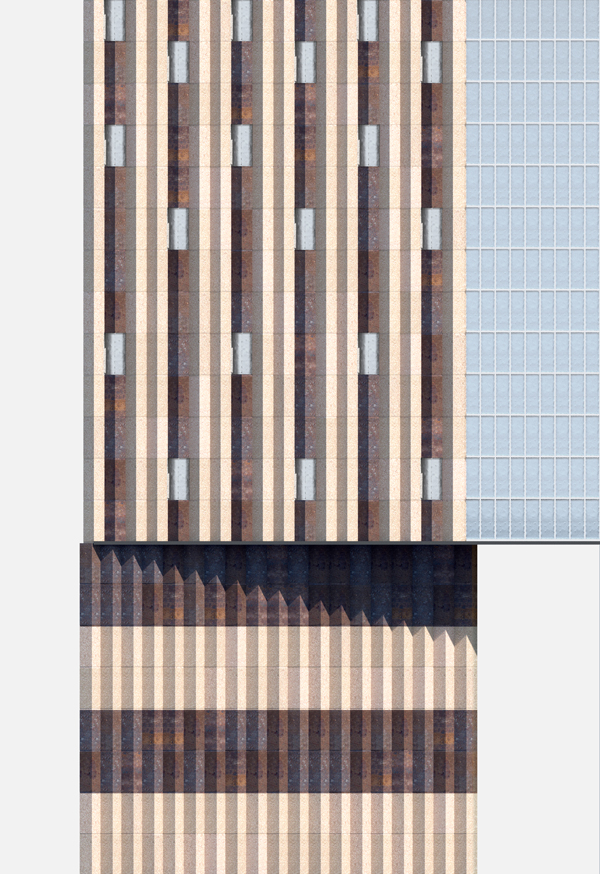

The new entrance for the building is clearly demarcated by a new masonry lift tower, made from strongly patterned, carefully angled and cut recycled brickwork set back from the street, which stands in opposition to the existing clock tower as a sort of resistance to colonial architecture. The additions carefully consider their materiality and composition, and the effects that light and water will have over these materials over time. The use of recycled building materials is maximised – using bricks, stone and timber reclaimed from nearby demolished sites – as well as maximising locally produced materials, trades and training programs. Using the same materials as the existing building, but in a contemporary way that respectfully acknowledges and celebrates their origins from this Country, the entry finds a new way of moving into a colonial space through a new, dedicated and celebratory pathway.

In one of our first conversations with Danièle, she drew to our attention the writing and research of the Bawaka Collective – an Indigenous and non-Indigenous, more-than-human research collective. In their paper ‘Co-becoming Bawaka: Towards a relational understanding of place/space’, they ask us to “consider an Indigenous-led understanding of relational space/place” drawing on the concept of gurrutu to “look to Country for what it can teach us about how all views of space are situated.” Gurrutu recognises all relationships within Country. It recognises us as just one part of the broad and interconnected network of all things that constitute Country.

Considering this way of thinking and working – recognising ourselves as just one part of a much broader and significant network – has framed our approach not just for this project, but for all projects that we undertake as a practice. Emphasising a relational understanding of time and place, and where we sit as architects within it, we feel is hugely important to ensuring a respectful and valuable practice in architecture with in our communities, now and into the future.

Isabelle Aileen Toland is a co-director and co-founder of Aileen Sage Architects based in Sydney. She grew up in Guringai Country and currently lives and works on Gadi land. Isabelle graduated from the University of Sydney in 2003. She has worked overseas in Paris as well as in Sydney for Neeson Murcutt Architects where she and co-director Amelia Sage Holliday met and worked for several years prior to establishing Aileen Sage in 2013.