Liehan Janse van Rensburg recently caught up with Yolandé Vorster of Conrad Gargett to talk about her work, her experiences, and her journey towards specialising in heritage architecture.

We all have something to learn from what heritage architects do. Knowledge and respect for heritage is not only about the past – but also about dealing with our current work as ‘future heritage’.

Read on for some great insights into what it’s like to work in this specialised field of architecture.

1. Why do you enjoy working in/with heritage architecture – and what drew you to it in the first place?

I love puzzles, and finding out as much as I can about topics that I’m interested in, such as figuring out the chemistry behind making my own ceramic glaze. So I’m not too surprised that I fell in love with heritage architecture where every project is complex and challenging, no matter what size it is. There is an inherent intricacy in working with existing built fabric, so I am constantly learning.

I have always had an affinity for old buildings, but living in the Netherlands during my gap year was my first introduction to such a richly-layered urban fabric. I wasn’t interested in studying architecture at the time, but when I look through my photos, I can see how captivated I was by the intermingling of old and new. I can still vividly remember a particular 15th century Gothic church that had been converted into a hotel, with a bold new entry down the side. Thankfully my mum had noticed my fascination with the built environment and encouraged me to do architecture.

Fast-forward six years to when I took a research elective looking at cultural landscapes, which quickly turned into my final year thesis. As the interface between the tangible and intangible, nature and culture, cultural landscapes challenged the traditional concept of heritage as being physical and immutable. This contributed to an international renegotiation of the scope and definition of heritage to include both tangible and intangible heritage. Considering the relatively recent shift away from physical heritage towards a concern for cultures, traditions and the intangible, I was interested in how the more intangible aspects of these sites, particularly at the World Heritage level, were being managed sustainably. I decided to focus my research on vineyard cultural landscapes, in light of the announcement that the Mount Lofty Ranges (which includes the Adelaide Hills and Barossa Valley) were in the process of bidding to be World Heritage listed. I was interested in understanding how the living, continuing nature of working vineyards affected the protection, conservation and future development of these sites. This journey into the management of the significance of heritage sites is what ultimately drew me to working in heritage architecture.

2. HOW DO YOU BECOME A HERITAGE SPECIALIST?

Like many specialties in architecture, this is something that happens through experience and time. I work with a number of heritage specialists who have gained a wealth of knowledge simply by working on heritage projects; while others have supplemented this with internships at the Getty Research Institute/ ICOMOS/ ICCROM, getting hands-on experience with the conservation of built fabric, working for council or doing degrees in history or the conservation of heritage monuments and sites. While some universities offer these heritage architecture-adjacent degrees, the path to becoming a heritage specialist isn’t that prescribed. Most of my knowledge has been gained from working on projects, developing relationships with specialist trades people (such as brick specialists and stone masons), and asking the rest of the Conrad Gargett heritage team lots of questions. I am also getting into the reporting side of heritage architecture, such as producing Heritage Impact Reports and preparing Exemption Certificate Applications.

I am currently working on my first ‘conservation only’ project where the scope of work is almost entirely focussed on repairing and stabilising the built fabric.

Built in 1864, the former National School building, at Warwick East State School, is one of the earliest surviving government school buildings in Queensland. For this project, we worked very closely with a brickwork specialist in order to identify the extent of deterioration from over 150 years of intermittent flooding, and to determine the scope of conservation work required. Documenting this project was quite different from traditional projects, and pushed me to expand my architecture lexicon. I learnt to identify areas of efflorescence; where salt had built up on the surface of the bricks and was starting to disintegrate them. In order to start repairing this, and minimise further efflorescence, the many layers of plastic paint were removed so that the brickwork walls could breathe again. A few rounds of poultice was then applied to the walls, which is basically a special paper mache mixture that draws out the salts from the brickwork. Our next move will be to replace the cement mortar with a lime-rich mortar, so that any moisture in the walls escapes through the less-dense lime mortar rather than the brickwork. This mortar can be replaced easily once there is a build up of salts; reducing further deterioration of the brickwork.

3. What are some challenges you’ve faced working in heritage architecture?

Firstly, I had to let go of some of my perfectionism because walls and floors in old buildings are rarely perpendicular, and dimensions don’t round nicely to whole numbers. Thankfully, there is a range of technology to help us capture built fabric nowadays, such as point cloud scanners and matterport scanners, but even these require a generous level of tolerance. So there is a lot of measuring and re-measuring, and a lot of ‘align’ notes to indicate the anticipated relationship between surfaces.

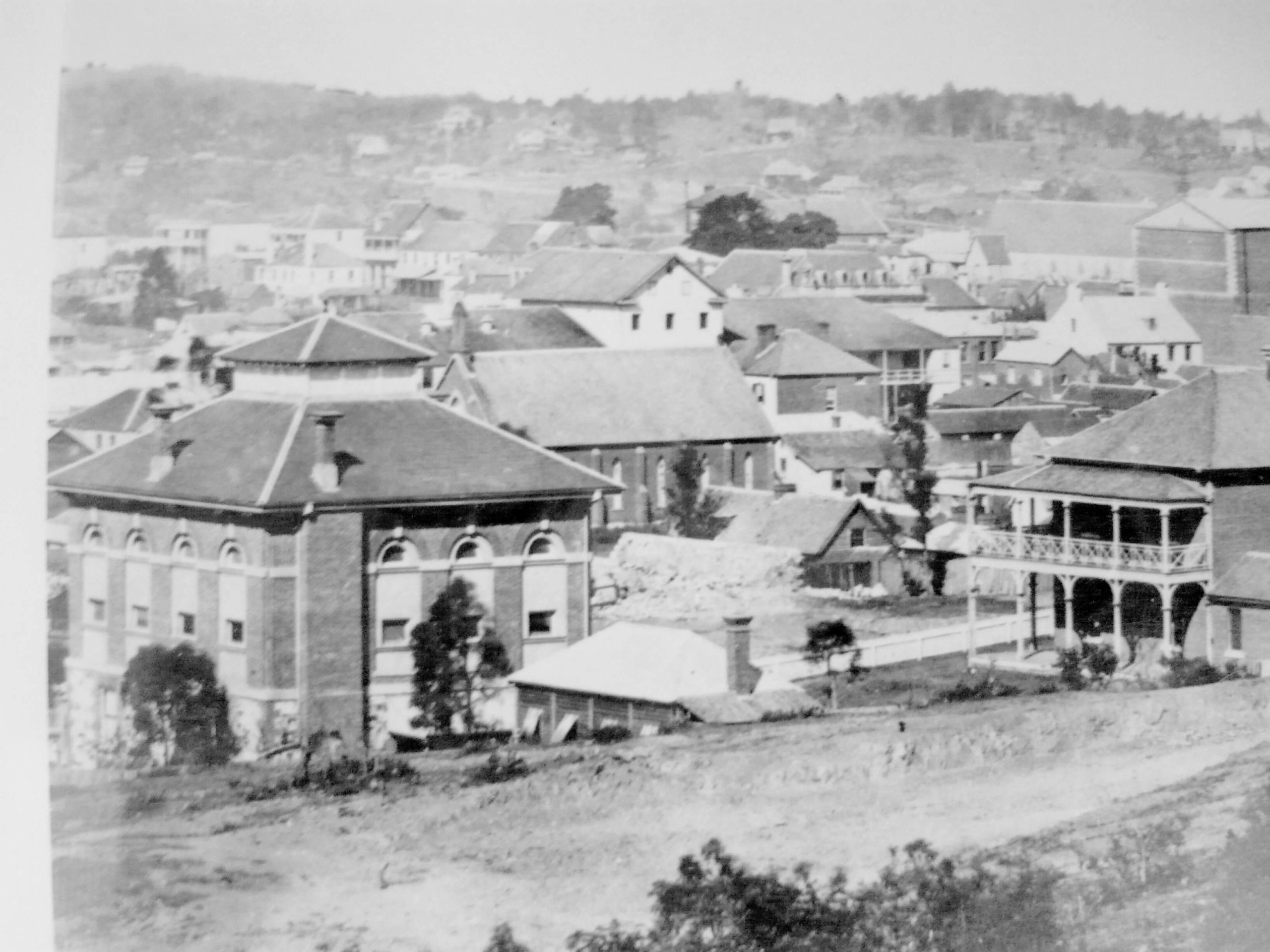

The other challenge is figuring out the age of various elements, which can be tricky when parts of the building have been rebuilt to match the original, and there is little existing documentation available. For the Brisbane School of Arts (former Servants Home), Conrad Gargett had done an extension in 1908, so we were able to dig out some drawings from our archive for that part of the project; but untangling the history for the rest of the project required a lot of detective work. We spent hours going over old newspaper articles, purchase orders, photographs, old surveyor’s drawings of the city and descriptions of proposed scope of works. We also spent time on-site getting input from specialist tradespeople, inspecting opening up works and reviewing paint scrape analyses. It is exciting discovering new details each time we visit the site, and sometimes find unexpected details such as a cut-off piece of timber under a floorboard – signed and dated by the people who laid the floor. Sometimes we’re fortunate enough to work on a building where someone else has already done most of this research and integrated it into a conservation management plan; but other times we need to do this ourselves.

4. Are there any particular advocacy issues in the field of Heritage Architecture at the moment?

While there are systems in place for buildings that have already been assessed as being of state or local heritage significance, there is a gap in advocacy for our more modern heritage. This is becoming more evident with the increase of significant buildings coming under threat, and the list of projects that have already succumbed to these threats. This is where DOCOMOMO (a non-profit organization for the Documentation and Conservation of Buildings, Sites and Neighbourhoods of the Modern Movement) can play a role in advocating for the protection and heritage listing of significant projects. DOCOMOMO is made up of a volunteer group of architects, historians, conservationists, and enthusiasts who prepare listings for significant projects, and submit these for review to be included on the DOCOMOMO list of projects at risk. From this list, projects are then selected to be submitted for inclusion on state or local heritage lists. It often takes a few attempts for a project to make it onto the state or local heritage lists, so it is crucial for this process to start prior to the building coming under threat. This is why DOCOMOMO is so important – to both identify our future heritage and prepare listings that will allow the buildings to be submitted for state or local heritage listings without too much more work.

The DOCOMOMO chapters in Victoria and New South Wales are quite active, but the Queensland chapter has not been active for years. This is something that the heritage team at Conrad Gargett is looking to change by contributing to the list of projects under risk in Queensland. It is our hope that this will reinvigorate, and eventually re-establish the Queensland chapter.

5. Why is DOCOMOMO important to all architects?

DOCOMOMO is important because it causes us to evaluate the threats facing our modern heritage, whether it is deterioration of the built fabric, or the threat of demolition due to a floor plate that is difficult to adapt to new uses. This in turn will hopefully foster discussions around sustainability, longevity and adaptability in design, because every new project has the potential to become future heritage. And we need to start protecting that heritage now.