SOFT THRESHOLDS AND STRONG GOVERNANCE: Cycling the edges of Copenhagen

We began the day with a literal shock to the system – plunging into the icy waters at Kalvebod Bølge along Copenhagen’s harbourfront. It was a fitting introduction to a city that doesn’t just welcome bold moves – it’s built on them. Over the past decade, Copenhagen has transformed itself through design, using architecture as a tool to shape behaviour, support public life, and soften the edges between the built and natural environment. That early dive set the tone for the first day of the 2025 Dulux Study Tour.

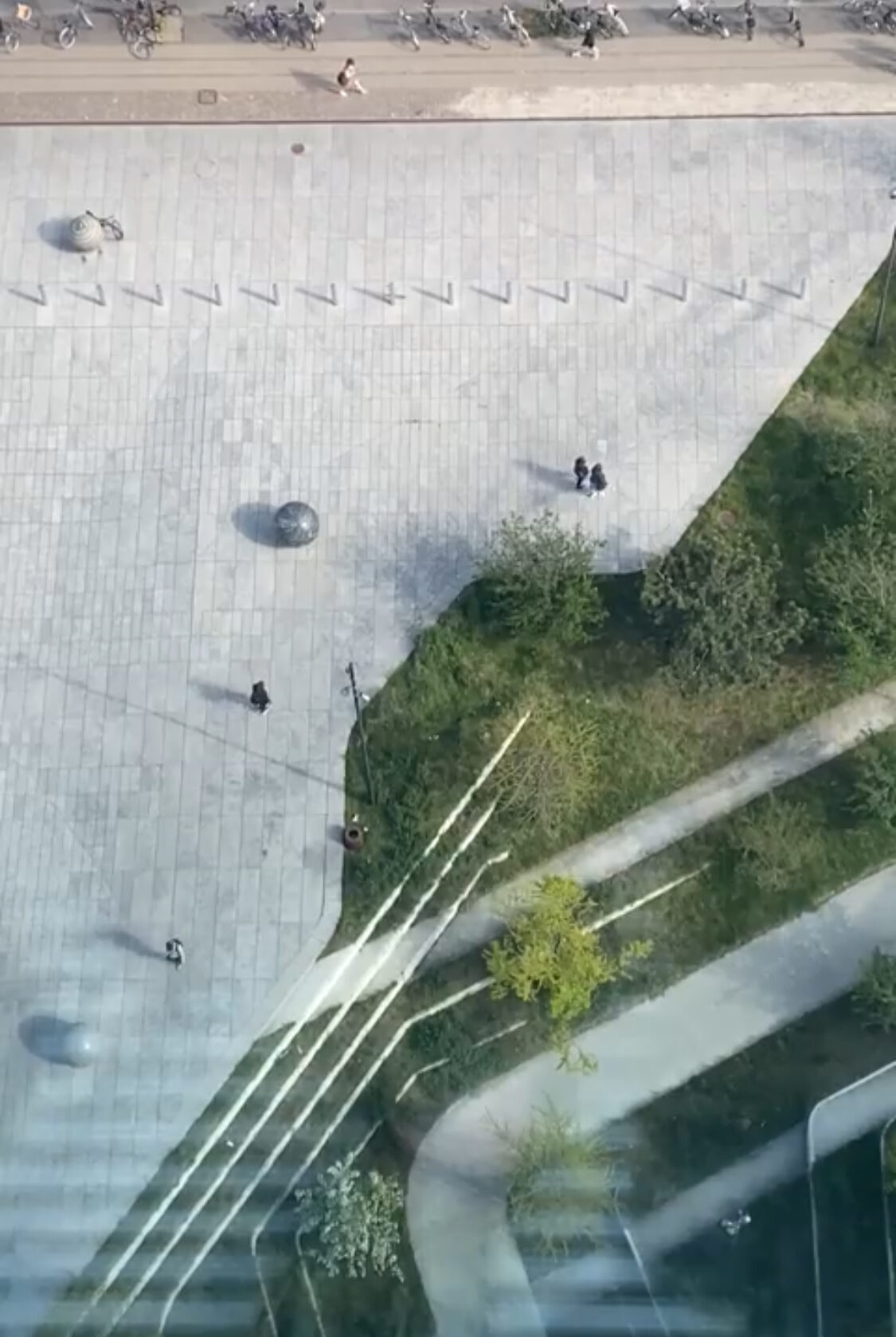

As we cycled through the city, it became clear that Danish architecture has evolved beyond the icon. The focus has shifted to the edge condition – where building meets street, and the private recedes to make room for the public. These are not hard boundaries, but soft thresholds: curved, generous, sometimes playful, always intentional. Architecture here yields – making space for a tree, a bench, a child’s game, or a moment of pause. This isn’t incidental. A choreography instigated by some of the big-name architects in town, it reflects a culture where design and policy work in concert to prioritise public life.

Our guide, Alice, who previously worked with the City Architect’s office, reminded us that “architecture shouldn’t take more than it gives.” In Copenhagen, buildings feel like they belong to the city—not the other way around. What’s particularly striking is how this generosity of space emerges from clear civic intent. Gerard Reinmuth from TERROIR called this the poetry of pragmatism. The Danes have invested in design excellence through design governance.

As an Australian architect, I couldn’t help but reflect on what this might mean at home. At our national conference this year, all state Government Architects were awarded the National President’s Prize – a recognition of the vital role design leadership plays in shaping public outcomes. And yet, over dinner with Scott Balmforth, director at TERROIR and strategic architectural and urban design advisor to Infrastructure Tasmania, I was reminded that in Tasmania, we can’t even officially call him a “Government Architect.” The title is avoided despite the work aligning with the position description.

That reluctance speaks volumes. While Copenhagen has embedded design thinking into policy to become one of the world’s most liveable cities, we still too often treat architecture as an aesthetic add-on rather than a mechanism for structural change. In Tasmania – Australia’s most socio-economically disadvantaged state – this is a missed opportunity. Copenhagen’s model shows what becomes possible when design is embedded not just in form but in governance. It’s not just about better buildings – it’s about building better lives.